Dear Delegate or World Leader,

It is probable that you will be taking a limousine or a helicopter to your hotel and conference venue when you arrive in Osaka this month.

The helicopter makes sense. Osaka is big. Those of you familiar with megacities in China, say, or Brazil, won’t find this a shock. Europeans might know the figures – more than 19 million inhabitants, 223 square kilometres – but seeing the megacity laid out before you is another matter.

As your unpaid advance man, I took the airport limousine bus. I highly recommend this mode of transport. It’s an opportunity to share legroom with ordinary people – you know, the ones whose fates and futures you’ll be deciding. But it’s also a memorable way into the city. For an hour, your coach travels along the raised motorway. It’s a waist-high experience of the place as you wade through a sea of illimitable economic activity: offices, factories, hotels, residential blocks, on and on and on.

Even the bankers and finance ministers among you cannot help but be awed by the commercial might of a city that was a megapolis when your home cities were barely more than overgrown market towns.

Finally, you coast down from the motorway – the recorded message warns there might be delays, but there won’t be any: this is Japan.

I stayed, as many of you will be staying, at The Ritz-Carlton. This is in the business area of Umeda, and it’s familiar turf for you: a premium-listed international district of tower blocks with luxury shopping brands adorning the lower floors, wide streets for 4WDs and limos, and a discernible sense of aloofness from the real hubbub of the city.

Step through – or be ushered through – the hotel’s door and you are in a cosy atmosphere of international prestige and affluence. The designers modelled the public areas on an 18th century British noble’s stately home. You get antique coated mahogany panelling, original oil paintings and a warren of high-ceilinged rooms housing boutiques, chocolatiers and the like.

Of course, I wanted to know who will be in the presidential suite come 28 June. Of course, they wouldn’t tell me. It is 2,500 square feet of conservative opulence – with a grand piano overlooking the city and Osaka Bay beyond. I searched ‘world leaders who play the piano’ and it turns out that France’s President Macron trained on the instrument at the Paris Conservatoire: so, let’s hope he gets it.

There was a black-tie charity dinner on my first night at The Ritz-Carlton. You would undoubtedly have been invited. I wasn’t, so I set off to find a bowl of udon noodles, some sashimi and a cold beer at nearby Osaka Station. This I did, and very tasty it was, too: though the public health experts among you might want to take the Japanese prime minister aside and offer some advice about banning smoking in public places.

You will have a busy schedule of meetings, side meetings and official functions. But I do hope you find time, as I did, to visit Osaka Castle.

It’s an impressive sight now, surrounded by a fearsomely deep double moat. But imagine it at its peak in around 1600: the fortress of all Japan, where the daimyos, or noble warlords, met to sort out the turmoil after the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi – Japan’s second great unifier.

You may know the name of the daimyo who emerged victorious after sacking the castle and launching a shogunate that would last for 268 years: Tokugawa Ieyasu. If not, you need to go back to statecraft school. Ieyasu was one of history’s supreme dealmakers and dealbreakers. He was a serial manipulator of pacts and people. And though he ushered in a long era of peace in Japan, note this: there are those among your hosts who see him as a blatant opportunist rather than a national hero.

Still, by all means pay your respects to Ieyasu at the castle’s excellent museum: you’ll see his seals and many wall panels showing the ‘summer siege’ that brought Osaka, and the country, under his sway. Whether he was a good thing for Osaka thereafter is a matter of opinion. He moved his power base to the obscure town of Edo to the east. Shorn of its power, Osaka spent the years of the Tokugawa regime doing what it liked most: making money, eating, drinking, watching scandalous kabuki performances and thumbing its nose at Edo.

What it couldn’t do, much, was trade: a serious blow for a city that had built up a good business with merchant adventurers from Portugal, Holland and England. Ieyasu’s successors put a stop to all that as the period of self-imposed isolation from the world known now as sakoku took hold. It wasn’t until 1853, and the arrival of Commander Perry’s American warships, followed shortly after by an even more determined British expeditionary force, that the trade barriers were brought down – and with them, the Shogun’s world. There followed a new era of industrialisation and Westernisation. Osaka Castle burned down and was rebuilt – twice.

The free-trade, anti-isolationists among you will enjoy that lesson from history. They didn’t want to invite in the outside world. But when they did, Japan became a great world power. Edo got a new name (Tokyo); Osaka stayed Osaka and carried on having fun while getting bigger, richer and bigger still.

If you have time, wander over to the striking Osaka Museum of History right next to the castle. It’s not only the story of the city – it’s a microcosm of waxing and waning East-West relations.

But Osaka isn’t just a place to ponder history and statecraft: there are photo opportunities to be had.

The photo-opportunists of the Instagram kind are most out in force at the Kuromon Ichiba food market and the crowded food and shopping streets around Dotonbori.

credit: Irwin Wong

I hopped on the short Tombori river cruise in Dotonbori and I fervently hope the Osaka hosts persuade the leaders of the world to do the same.

Osaka’s waterways are more about quantity than quality. I doubt the Italian delegation will be reminded much of Venice as they step onboard the cheery yellow boat under the giant Don Quijote shop frontage. The British party, however, may be transported back to the industrial canals of their own second city, Birmingham.

No matter. The G20 leaders should clamber onboard and, in a positive declaration of unity and fraternity, each don one of the free plastic macs the operators keep in case of bad weather. You’ll enjoy the short cruise. Everyone on the bankside cheers as the boat goes by. For any leaders suffering difficulties at home, it’ll be a welcome reminder of what people waving happily at you feels like.

You’ll then want to head off to Tsutenkaku.

This jaunty iron tower was opened in the flush of post-Eiffel, exhibition park construction in 1912. At that time, it was the second-highest tower in Asia. Today, you may struggle to see it until you’re in the lively, izakaya-filled streets of Shinsekai.

In its own way, this long-standing palace of fun (‘all things are gilded and shiny!’ cries the brochure) is a tribute to international relations. The observation deck is devoted to a charm doll invented by a Kansas woman in the early part of the 20th century: the Biliken, or ‘the god of things as they ought to be’. A model of this cheery, elephant-alien-Buddha character sits with his feet turned up, and visitors rub his soles and pray for things to turn out as they should. Delegates involved in international diplomacy might wish to do the same.

There is a more tragic reminder of what happens when things do not turn out as they ought: a film of a flattened and fire-bombed Osaka at the end of the Second World War. It’s a small miracle that the tower, built in a very different era of US-Japanese relations, survived.

Finally, the basement harbours the Biliken’s Mouth of Truth – a must-see for your press attachés and media relations teams.

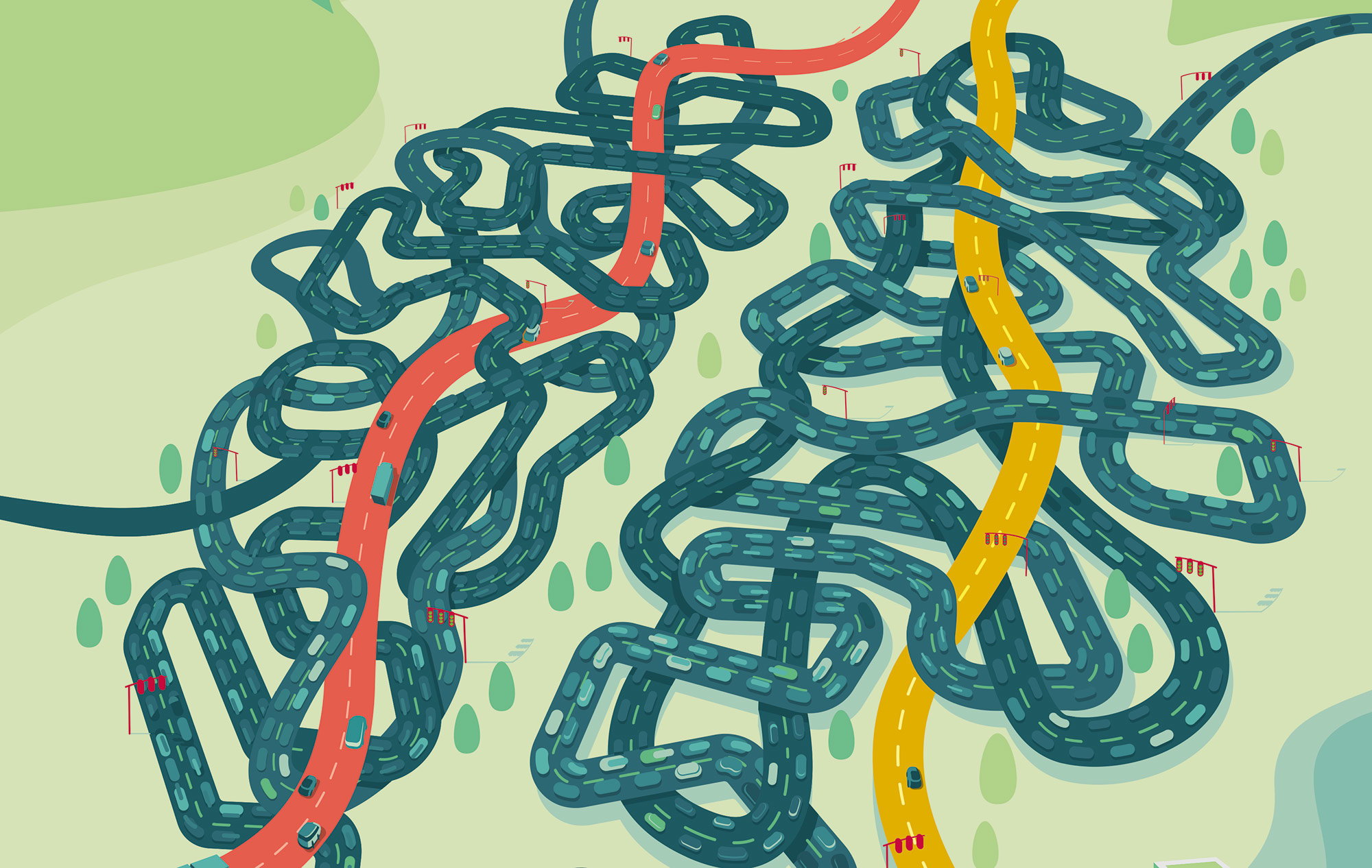

I should warn you that the city can be a maze. On returning to Umeda, I spent a befuddled 45 minutes trying to take what should have been a five-minute walk to The Ritz-Carlton. As I was taken underground when I wanted to be at street level, out of – and back into – the gargantuan station complex time and time again, I had an inkling of life on the international diplomatic frontlines. Anyone from the British delegation who has been involved in the Brexit process will be familiar with that Osaka Station feeling: you go round and round in circles getting ever more stressed and cross, before ending up very much where you were before.

But in the end, you do find an escape route. I got back to the hotel, packed and wheeled my case to the bus stop. The airport coach officials bowed, and we were off along that long motorway again. The sun appeared, clouds hung epically over the world of Osaka and, eventually, the wide expanse of calm, sunlit water around Kansai International Airport came into view. After three days in this immense, welcoming, bewildering city, I’d rather forgotten there was a world outside. You may find that familiar, G20 delegate.

Cathay Pacific flies to Osaka from Hong Kong 42 times a week