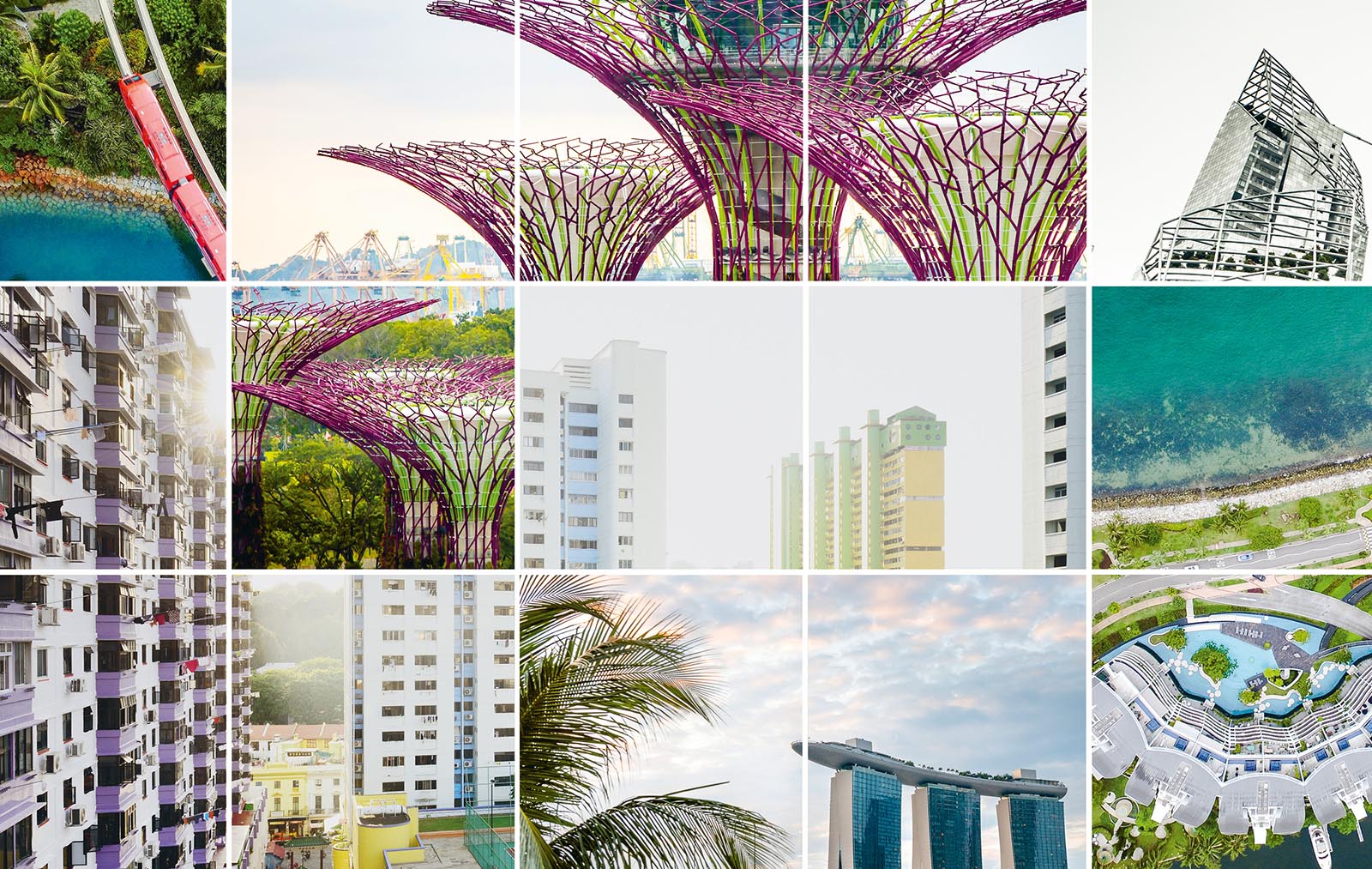

Discovery is predicting that three trends will dominate travel in 2018: the renaissance of northern Europe; the rise of Asian heritage projects; and an increasingly sophisticated health and wellness tourism industry.

Here we explore how Asia’s oldest buildings are paying back, and in a second piece pick out Hong Kong’s Tai Kwun project for a special report. Click here for that article.

It’s a deceptively simple narrative. Europe preserves and values its built heritage. In Asian cities, breakneck growth and untrammelled modernity rule – and if some old buildings get in the way, so what?

But sometimes narratives are too simple. This one understates how much in Europe and America has been lost to the planners rather than the bombers – and how much was only just saved. Today, places like Amsterdam, New York’s Greenwich Village and London’s Covent Garden attract millions of tourists. But in the 1960s and ’70s Amsterdam’s canals were nearly filled in, Greenwich Village’s streets were scheduled to be replaced by a freeway and the neoclassical Covent Garden market building was due to be torn down. All three places were saved by the spirited opposition and campaigns of local inhabitants.

For whatever reasons, social or political, local protests on that scale are rare in Asian cities. Instead, the hope for its built heritage increasingly lies in the hands of individuals, entrepreneurs, the more far-sighted property companies and government departments, which are finding that saving the temples and the hutongs, the colonial headquarters and ancient lanes isn’t just a good thing: it’s good business, too.

Hong Kong has rarely been a good example to the region. But last November, Wan Chai’s Blue House was awarded Unesco’s highest conservation award for cultural preservation. The award rounded off a year of landmark heritage projects in the territory: the opening of The Murray, Hong Kong, fashioned out of a dour 1960s office block on Cotton Tree Drive; and District 15’s development project in Shek Tong Tsui, galvanised by its Yat Fu Lane retail project. There’s more: this summer will mark the grand opening of the Central Police Station, the largest scale heritage project in Hong Kong since Central’s Police Married Quarters was reborn as the PMQ cultural hub in 2014.

‘Over the past few years there has been a renewed effort to preserve these types of buildings,’ says Ester van Steekelenburg, founder of the campaigning group and tourism operation Urban Discovery. ‘It’s an Asia-wide thing: we’re seeing it in Bangkok, in Hong Kong, in Jakarta.

‘Take the old pre-war shophouses [such as those in Central’s Graham Street Market]. They weren’t deemed as valuable; they were seen as ordinary buildings. Now there is a realisation that not everything has to look the same.’

Alongside the ‘soft’ benefits that come from cultural preservation (more liveable cities, a sense of community) there are hard figures. Unesco and The World Bank claim that sustainable tourism will generate US$1.8 billion (HK$14 billion) by 2030, much of which will contribute to sustainability and the preservation of both tangible and intangible heritage.

And so governments and private developers are eyeing dilapidated buildings and neighbourhoods across some of Asia’s once-grand colonial cities and turning them into bars, cafes and co-working spaces.

Here are some of Asia’s latest and most eye-catching preservation stories.

THE HOTEL: AMANYANGYUN

WHERE: SHANGHAI, CHINESE MAINLAND

When Ma Dadong sold his Shanghai advertising agency, he needed a new challenge. How about moving Ming- and Qing-era buildings, brick-by-brick, and 10,000 camphor trees 700 kilometres from Jiangxi province to the edge of Shanghai? This month, the hotel he created with the Aman luxury resort group opens as Amanyangyun, China’s most ambitious heritage and hospitality project since The Temple House

opened in Chengdu three years ago. Also recently opened in the city is Capella Shanghai: a rethought French Concession boutique carved out of a cluster of 1930s shikumen buildings.

aman.com, capellahotels.com/shanghai

THE STREET: ESCOLTA STREET

WHERE: MANILA

A century ago, Manila’s Escolta Street was the Wall Street of the Philippines. It also held the honour of being the location of the country’s first ice cream shop as well as hosting the Philippines’ first lift (in the 1919 Burke Building). In the years that followed, the area’s grand neoclassical, beaux-arts and art deco buildings fell into disrepair as businesses moved to the growing Makati and BGC districts.

Fast forward several decades and the First United Building, now part-owned by the local Sylianteng family, has kicked off a regeneration campaign for Escolta Street.

The building is now home to The Den cafe, craft beer bar Fred and a co-working space; while other buildings house design outfits and museums. The Escolta Block Party, a line-up of talks, performances and open houses, celebrated its first birthday last November. ‘It suddenly made sense for the landlord to keep these types of buildings,’ adds Van Steekelenburg.

THE BUILDING: THE BLUE HOUSE

WHERE: HONG KONG, CHINA

The Blue House cluster, three pre-war shophouses – one painted in royal blue, another custard yellow and a third tangerine – on Hong Kong’s Stone Nullah Lane, demonstrates ‘a triumphant validation for a truly inclusive approach to urban conservation’, according to a Unesco jury when it won the Award of Excellence last year.

‘This unprecedented civic effort to protect marginalised local heritage in one of the world’s most high-pressure real estate markets is an inspiration for other embattled urban districts in the region and beyond,’ it added.

In Hong Kong’s fast-gentrifying Wan Chai neighbourhood, these timber structures were once a martial arts school and an osteopathy clinic. Today, its ground-floor levels host excellent Thai noodle joint Samsen and the House of Stories museum.

THE HOTEL GROUP: BELMOND

WHERE: YANGON, BANGKOK, LUANG PRABANG

The Belmond group has been particularly active in preserving some of the region’s grandest colonial architecture and infrastructure. Not to mention trains: its portfolio includes the Eastern & Oriental Express (top), which shuttles travellers between Bangkok and Singapore in renovated 1970s-era carriages fitted out with vintage lighting and upholstery. The Belmond Governor’s Residence in Yangon (above), a former diplomatic residence, is a handsome two-level teak villa with colonial additions including straw boaters and gauzy mosquito nets; while the La Résidence Phou Vao in Laos, which also follows the colonial teak wood creed, looks over Unesco World Heritage town Luang Prabang.

belmond.com

THE NEIGHBOURHOOD: KOTA TUA

WHERE: JAKARTA

Jakarta’s old city, Kota Tua, was once a walled town for Dutch colonialists, serving as the de facto capital of the Dutch East Indies. It fell into

decline at the end of the 18th century, as Jakarta’s movers and shakers moved to the city’s fringes.

Since being designated a heritage site in 1972 by the Indonesian government, Kota Tua has been regenerated thanks to the Konsorsium Kota Tua group and a generous cash boost.

Now, the area’s iconic Dutch architecture has been turned into exhibition spaces, concert halls and gentrified weekend markets. ‘It used to be a seedy place,’ says Van Steekelenburg, but this ‘incredibly exciting’ project has helped put Kota Tua ‘on the map’.