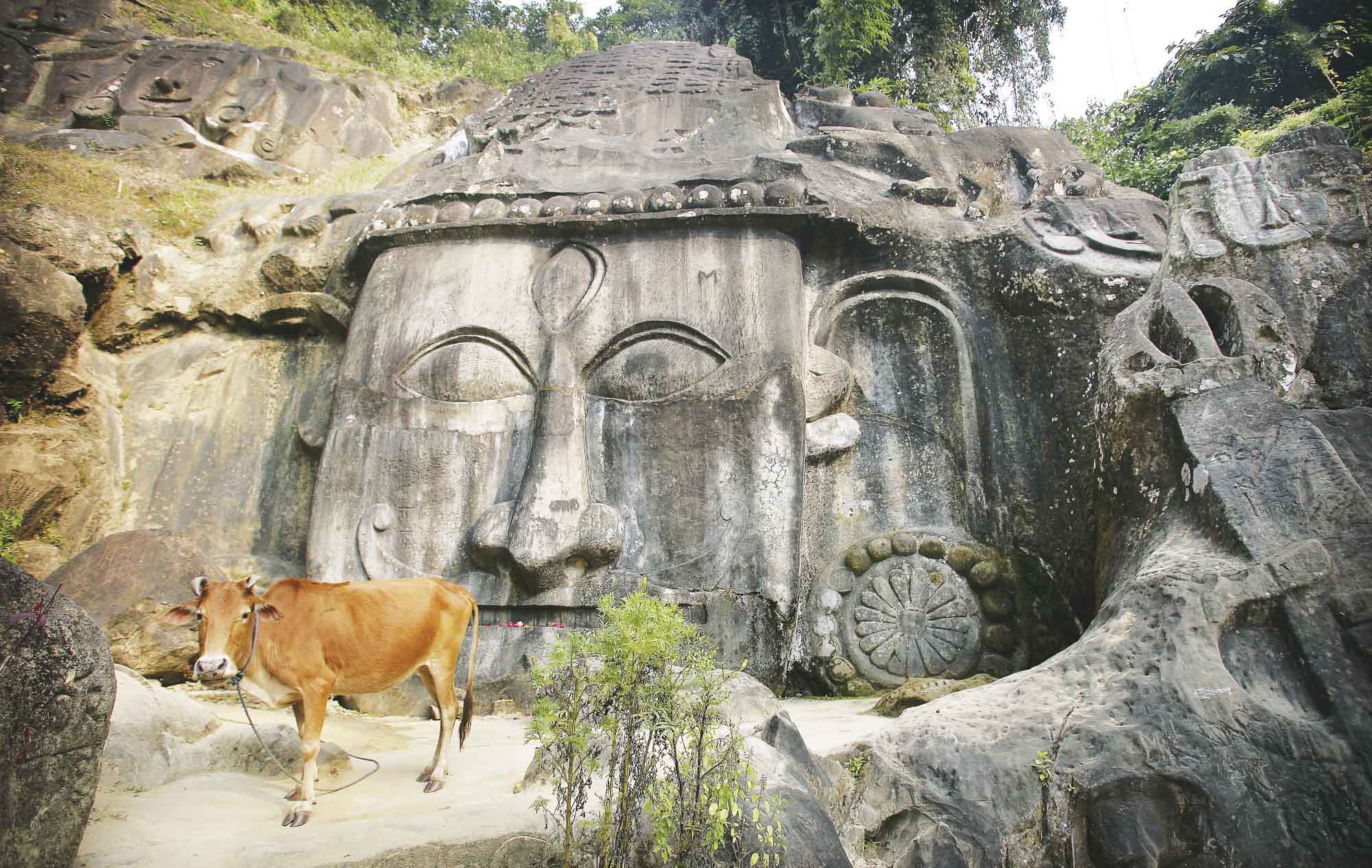

‘Turn in here,’ Dr Tathagata Neogi tells me. ‘This is amazing.’ I look up at the building we’re about to enter. It’s pretty non-descript, by Kolkata standards. Not colonial, hardly even old. Residential. Worn. I’m about to ask what’s so special about the building when Neogi ushers me through to the back courtyard, where four crumbling, 300-year-old temples stand, overgrown with moss.

‘Hardly anyone knows they’re here. They were built by an old rich family, but now everyone has forgotten about them,’ he says. ‘There’s so much history in Kolkata that people don’t know about.’

History, of course, is inescapable in the West Bengal capital, formerly called Calcutta. It was the East India Company’s most significant outpost, becoming the second biggest city in the British Empire at the end of the 19th century. The grand Victoria Memorial – completed by the British in 1921 and intended as a rival to the grandeur of the Taj Mahal – dominates the vistas across the city centre. And many of the city’s architectural and cultural landmarks – the stately Marble Palace, St Paul’s Cathedral, and the Indian Museum – evoke the days of its colonial wealth.

Yet its history runs so much deeper than the typical list of tourist attractions and quotable stats. Walk the streets, especially in White Town, the heart of colonial Kolkata, and there’s a story in every corner: small reminders of 300-year-old conquered forts, plaques in alleyways that commemorate milestones, buildings that were central to the entire global East-West trade of the past three centuries.

Neogi’s mission is to bring these stories to the fore. Last year, he founded Heritage Walk Calcutta, an organisation that conducts history-focused walking tours throughout the city. Neogi was born in Kolkata, trained and worked as an archaeologist before moving to the UK to do a PhD. During his spare time, he would visit the archives of the British Library, reading about the history of Kolkata, discovering stories and landmarks like the hidden temples, and realising how little he knew about his own city’s history. Then he had an epiphany.

‘I really wanted to start something to help connect locals with the history of Kolkata,’ he says. ‘Many locals don’t know much about their history, about the significance of these buildings. I really believe that showing local people the state of our buildings will impact how they think about heritage and conservation.’

Neogi’s background as an archaeologist also led to another important aspect of Heritage Walk Calcutta: all the tours are conducted by academics. ‘We really want to connect academics with our communities,’ he says. ‘In India, the two are so far apart. I think we academics have a responsibility to help, but to also learn and pass on the knowledge of our local communities.’

Karan Kumar Sachdev

Heritage Walk Calcutta currently conducts five different walks (several more are in the works), ranging from an exploration of White Town to tours focused on the city’s oldest Chinatown, other colonial areas around Kolkata and the broader renaissance of Bengal. But a lot of the magic in his walks comes from the facts gathered along the way: the story behind the city’s distinctive taxis, the rise and fall of the Kolkata Chinese sauce companies, the bizarre tale of the 19th-century automatic sweeping machine that’s now become a rubbish bin outside the courthouse, the historical context behind the fading glory of abandoned mansions once belonging to the city’s elite families.

One morning, I meet Tirtha Chakravarti on the Park Street Cemetery tour, a walk that tells the history of Kolkata through some of its most famous figures buried in this eerily beautiful graveyard. Tirtha was born in Kolkata and lived overseas for 28 years after university, only to return 15 years ago. ‘The city of my birth is so rich in history, but I’m just starting to discover the extent of it now,’ says the 66-year-old, who studied history at university and has gone on several walks with Heritage Walk Calcutta recently. ‘I feel like I know nothing about my city. But when you do one of these tours, it really brings this history to life.’

What also emerges from these walks, however, is the increasingly precarious state of much of the city’s built heritage. Many of the buildings are crumbling. Even more have been abandoned. One formerly grand mansion that we pass has collapsed since Neogi last did the walk a week earlier. ‘I think showing a local person the state that their heritage is in can impact a lot on their consciousness,’ says Neogi. ‘I hope it will help people understand the importance of what we might soon lose.’

The walks are just the beginning for Neogi. He’s already started various community projects, including to translate some of the fading plaques of the original Chinatown and to produce a web documentary series telling some forgotten stories of the city. But his ultimate dream?

‘My long-term plan is to start an institute where you can teach the importance of community-led conservation,’ says Neogi. ‘But, actually, the main thing is to make people start talking about their own family history and experiences. That’s the conversation I hope we can really help start.’

Visit heritagewalkcalcutta.com to learn more