Teenagers in tie-dyed t-shirts are draped around industrial black and yellow striped columns. These hazard lines for fork-lift trucks are covered in a writhing, seething mass of blissed-out revellers – some catatonic, others whirling dervishes – as the bellowing beats reverberate around the cathedral-sized space.

This is the Hacienda nightclub, Manchester, 1988. A group called The Stone Roses are about to release their first record. In the years to come, a mash-up of electronica and psychedelia fuelled by various legal and illegal chemicals will create ‘Madchester’ – and one of those interesting intervals in British social history when it was here, rather than London, that innovation in culture, industry, music and fashion flowered.

The pages of fading newspapers and academic journals show us more of these moments. In the late 18th century, as the industrial revolution began in this corner of Lancashire, there were thinkers who believed that Manchester was the future: a more egalitarian society based on industry and graft as opposed to the class-ridden snobberies of London. Manchester became an alternative ideology as well as a place name: the city rattled the Establishment good and proper. It still does.

Revolutionary spirits love it here. The co-author of The Communist Manifesto, Friedrich Engels, was a resident in the 1840s. In the 1960s and ’70s, a raft of outsiders found that Manchester was the perfect place to shape their own future creative direction. Bob Dylan went electric at the city’s Free Trade Hall in 1966 to a crescendo of boos from disgruntled traditional folk music fans who abhorred the electric guitars he now relished.

‘It rains quite a lot in Manchester,’ admits local music historian CP Lee when we meet outside the Free Trade Hall (it closed as a music venue in 1996). ‘It might sound silly to some people but the weather is a massive contributing factor as to why Manchester has always been such a powerhouse of music and art. Rain means a lot of creative people tend to be indoors, in their studios, bedrooms and warehouses creating things. This city seems to have such a desire to create magic in the everyday world.’

With this comes a sense of slight intimidation. Mancunians have a reputation for not suffering fools gladly, for being blunt and for living in a city that still conjures up images of grinding cotton mills and terraced, rain-sodden Victorian streets.

Strolling across the Santiago Calatrava-designed Trinity Footbridge on a sun-dappled afternoon, voluminous clouds scudding across the horizon and the white lines of the bridge glinting like the strings of a harp over the River Irwell, the sense of renewal in this city is overwhelming. Those old images of Manchester are as distant to today’s locals as visions of a London where everyone wore bowler hats. And the days when the ‘real’ Manchester football team, City, languished in the lower reaches of the leagues, will be finally forgotten as manager Pep Guardiola’s team of expressive superstars canters to the Premier League title.

‘For a long time Manchester had quite a defensive attitude and wasn’t good at taking criticism from outsiders,’ says Chloe Travis, a 27-year-old tour guide. She’s browsing the Manchester Craft and Design Centre, a 19th century former fish market in the city’s creative Northern Quarter that’s now home to dozens of artists’ studios where jewellery, collages, crafts and paintings are sold. ‘The confidence is sky high at the moment. I’ve lived in this city all my life and I can never remember feeling as proud of it as I do at the moment.’

But what would it take for this to be more than a moment – more than the industrial miracle of the 1850s or the fashion burst of the 1990s?

A survey by pollster YouGov in 2015 proved what Britons already knew: Manchester is England’s second city. Now one newspaper wants to go further and make Manchester the country’s first – supplanting London.

The pretext is that the country’s seat of government, Westminster, is in a mess: a literal mess, as the 19th century palace where parliament meets undergoes a £4 billion (HK$43.7 billion) restoration programme. The Economist had a simple solution: move the capital to Manchester. It has, the newspaper argues, the infrastructure, not just to accommodate the politicians, but the big companies and ambitious entrepreneurs already impressed by its international connections and fast-expanding airport.

The country needs to be much less reliant on London, the piece went on: the Brexit vote was as much a vote against the capital’s cultural and economic dominance. Making Manchester the capital would ‘reshape the country’ and allow the city to ‘become a global power centre befitting Britain’s importance’.

Will it happen? No. But that Manchester as the capital of England is even worthy of serious discussion tells you one thing: that the city, like its football teams, likes nothing better than putting one over the folks down south.

Additional material by Mark Jones and Cathy Adams

Manchester’s aural history

Six albums from era-defining Mancunian bands

Joy Division, Closer

The baritone voice of the late Ian Curtis documents the isolation and anomie of late ’70s Manchester.

The Smiths, The Queen is Dead

Witty, scathing and at times almost unbearably touching, Morrissey and Marr’s 1986 masterpiece defines the essence of northern humour and pathos.

New Order, Technique

Early visitors to the burgeoning mid-80s Ibiza club scene, New Order (formed of the remaining members of Joy Division after Curtis’ death) returned home to create a dance classic where chilled Balearic vibes bedded down, unforgettably, with distinctly urban jackhammer breaks.

The Stone Roses, The Stone Roses

Full of psychedelic funk, arthouse rock and wistful lyrics of love and revolution, the band’s 1989 debut is a Mancunian dreamscape that hasn’t aged one iota in the three decades since its release.

Oasis, Definitely Maybe

Arrogant, swaggering, cocky and one of the biggest selling albums of all time; it may only be rock’n’roll, but few have ever done it better than the Gallagher brothers’ 1994 debut.

The 1975, I Like It When You Sleep, for You Are So Beautiful, Yet So Unaware of It

Hookworm riffs and an ability to encompass any emotion and make it their own, the 1975 are showcasing the future of astonishing breadth of Manchester music right now.

Old, new and good Manchester

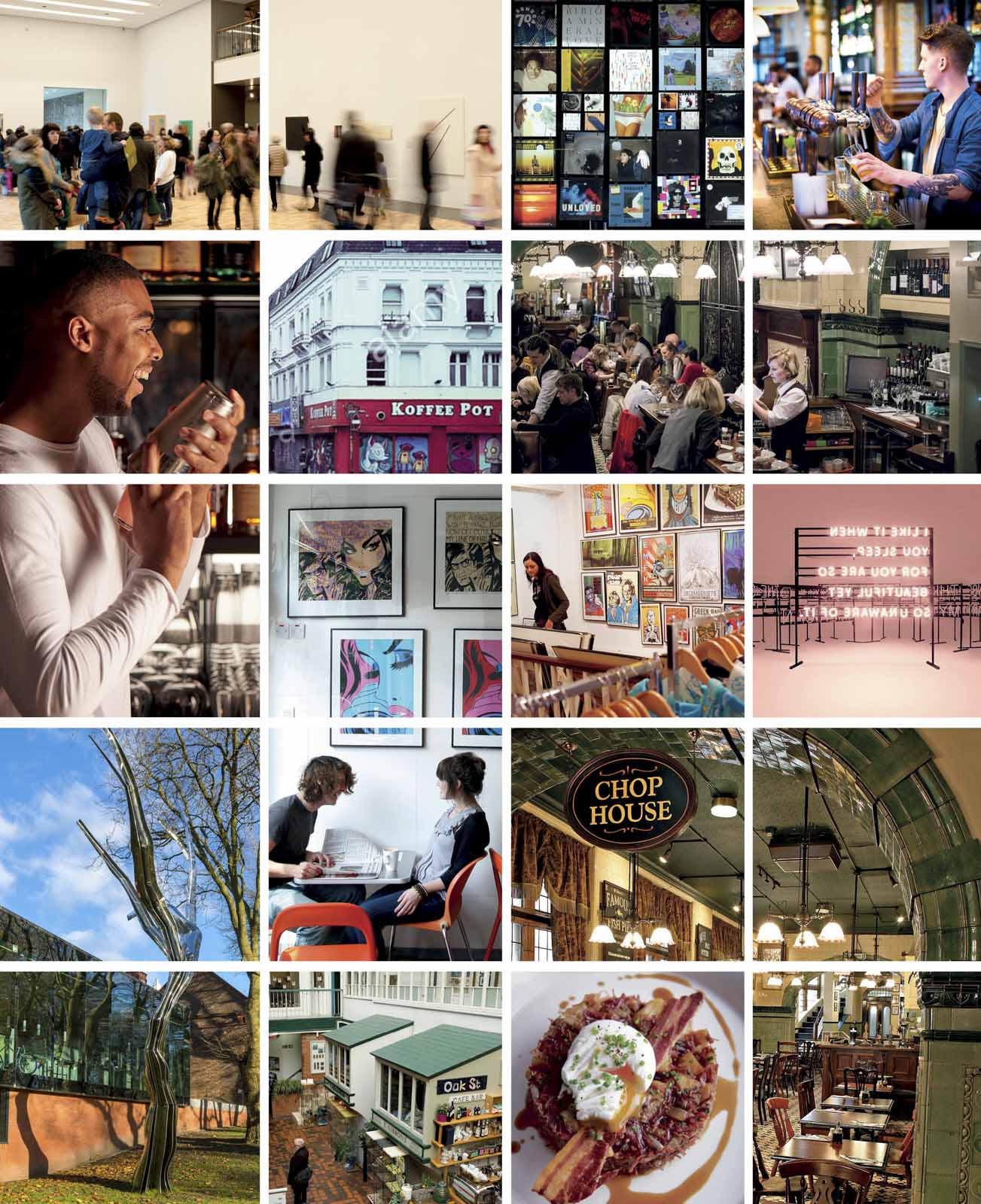

Eat

Unctuous lamb chops and real ale in the renovated art nouveau interior of Mr Thomas Chop House. Chase it with expert mixology in the bar of The Principal hotel – an elaborately reimagined 19th century insurance office.

See

Paintings by LS Lowry in the Whitworth Art Gallery: the artist’s utterly charming ‘stick people’ portraits of early 20th century Lancashire cityscapes are beloved by locals.

Visit

Salford Quays – a creative and media hub that the BBC now calls home. Nearby is The Lowry, home to a collection of the artist’s work, as well as a performing arts space.

Wander

The Northern Quarter – a red-bricked, formerly industrial jumble of design studios, coffee shops and bars, home to all the international staples of newly found hipsterism (you can’t move for beards, tattoos, plaid shirts and tea dresses), as well as vintage emporium Afflecks Palace and cult record store Piccadilly Records.

Sit

In Sackville Gardens – a small park near the Whitworth Gallery. Sitting on a bench is a life-size bronze of computer science pioneer Alan Turing, a professor at the University of Manchester, by sculptor Glyn Hughes. Dying in obscurity, Turing and his achievements were posthumously embraced: this was the man who helped crack the Enigma Code during the Second World War. He is now considered the father of modern computing. In Sackville Gardens, the sculptor’s original Amstrad machine is buried underneath the plinth that lies next to Turing’s genial looking statue.