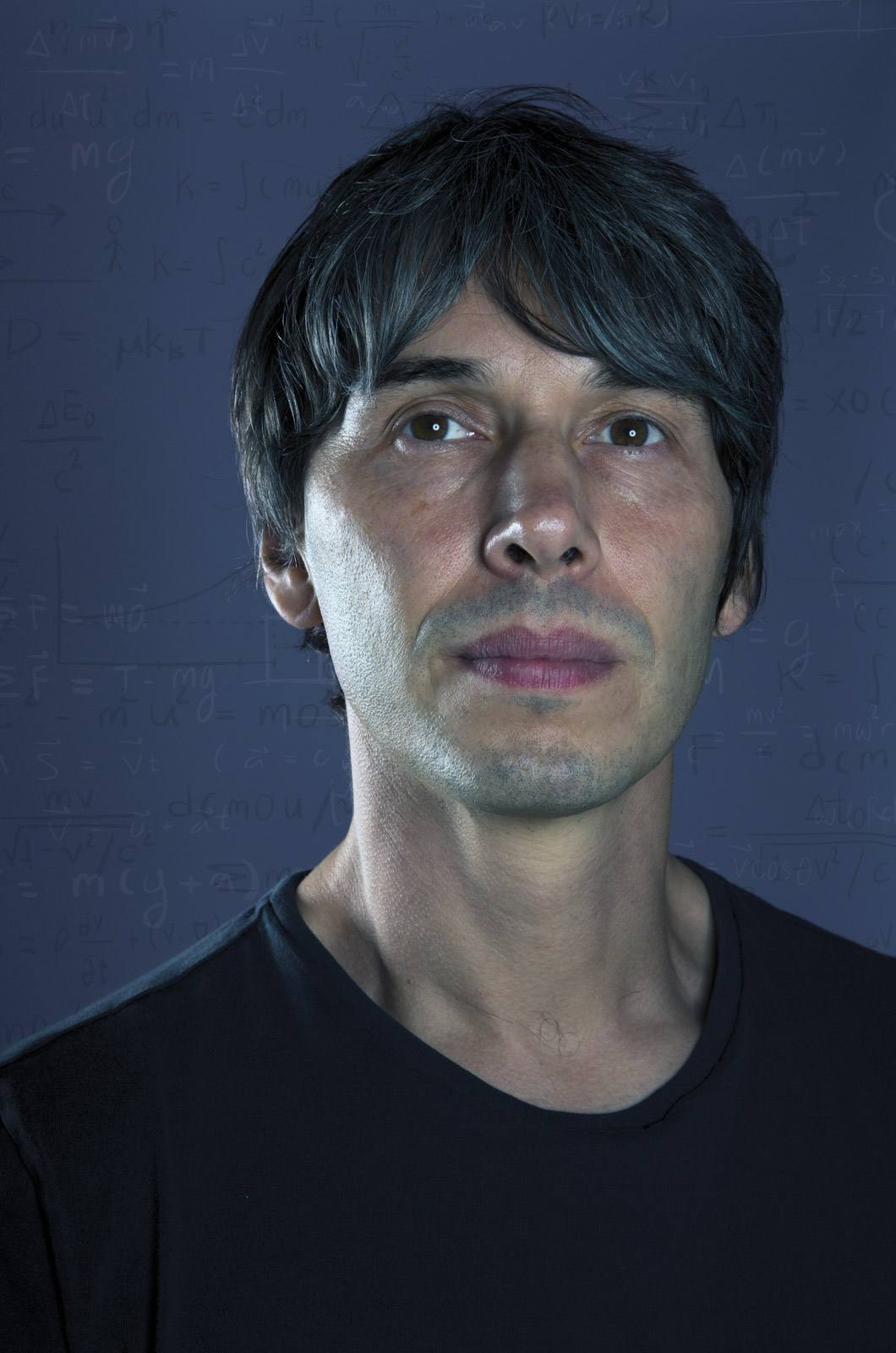

Eight years ago, a series called Wonders of the Solar System began airing on the BBC, presented by Professor Brian Cox. It was by no means the first programme to bring hardcore physics and astronomy to a general audience (Cox himself was hugely influenced by Carl Sagan’s Cosmos when he was growing up). But there was a twist this time.

‘The original, very good idea,’ says Cox, ‘was that we should use places on Earth as analogues for the solar systems and not rely so heavily on graphics.’

With that, a particle physicist with a Beatles haircut and a cat named after astronomer Caroline Herschel got to make some of the most memorable travel programmes of recent years. In explaining the universe to us, he showed us some of the most extraordinary places on Earth.

Wonders of the Universe followed in 2011. One of its first ‘analogous’ scenes was shot in Peru – used to explain the nature of time. He then stepped on a glacier in Argentina and also trod the sand of the Namib desert. The next episodes sent him to Kathmandu, New Mexico, Egypt and Zambia among others.

You have to like flying to do Cox’s job. Happily, he does like flying: a lot. The best perk he’s ever had was getting to fly in his favourite aircraft, the English Electric Lightning – similar to the one he first saw in Manchester’s Museum of Science and Industry. If he hadn’t become a rock star first (as keyboard player with the bands Dare and D:Ream), then an academic, TV superstar and public lecturer on a stadium scale, he says he ‘could easily have become a pilot. In the ’70s I used to go to Manchester Airport with my dad and write down plane numbers’.

But even as a TV presenter, he doesn’t believe TV is always the best way to get excited about science. ‘TV is no substitute. It can light the flame. But to go further you need to go to the places where science was done at the cutting edge.’

It so happens that many of those places are in England, his own country, and more than a few are within an easy drive of his birthplace (Saddleworth, Greater Manchester) and his workplace (Manchester University).

And so we asked Cox to create an itinerary of sites of really special scientific interest. Follow Cox’s Bespoke Tour and you’ll tick off the origin of time, the place where modern science began, the start of the industrial revolution, the origins of the modern world and the secrets of life itself.

The discovery: DNA

The place: Trinity College, Dublin; The Eagle, Cambridge

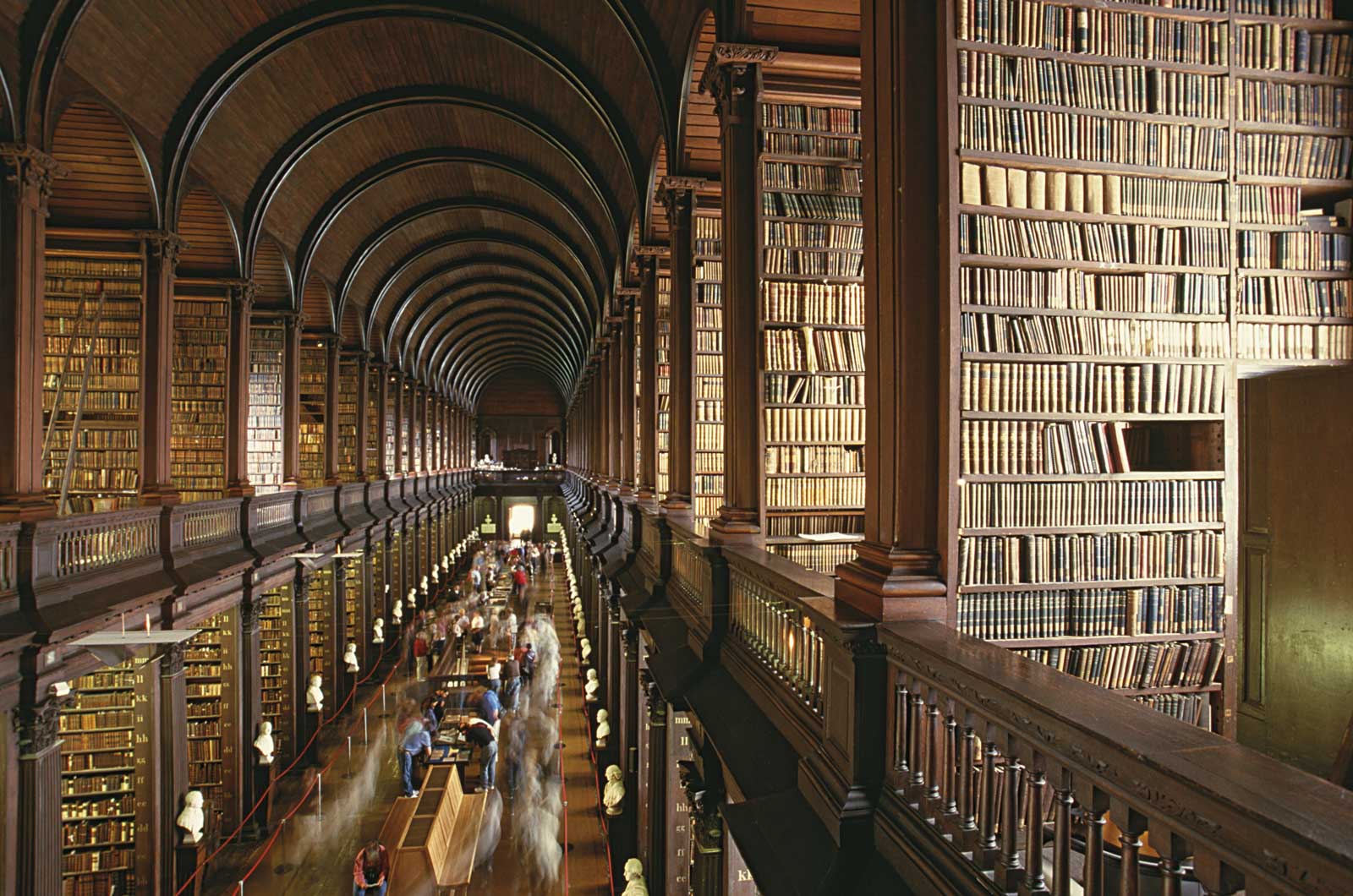

At the Institute for Advanced Studies at Trinity College, Dublin, in 1943, an émigré scientist called Erwin Schrödinger delivered a series of lectures that were eventually published as a book called What Is Life?

Cox takes up the story:

‘It was a radical book. A lot of it was about how complicated structures emerge. If you think about the human brain, it’s one of the most complicated structures we know of anywhere in the universe: yet the laws of thermodynamics state that things get less complicated and more disordered over time. How do you square the complexity of life with the basic laws of nature? That was the inspiration for my series Wonders of Life – all inspired by that little book I read as an undergraduate.’

(Schrödinger’s name today is usually linked to a cat: a very paradoxical and problematic cat it is, too.)

In What Is Life? Schrödinger mentioned the existence of an ‘aperiodic crystal’:

‘He’d worked out that you need some molecule to carry information from generation to generation.’

The hunt for this molecule was on. One lunchtime, a decade later, molecular biologist Francis Crick walked into The Eagle pub in Cambridge and announced, ‘I have discovered the secret of life itself.’

Inspired by Schrödinger, in partnership with James Watson and owing much to the pioneering crystallography work of Rosalind Franklin, the soon-to-be Nobel prizewinner had found that molecule – or rather two strands of molecules in a double helix structure they called DNA. (The Eagle now serves a pint called Eagle’s DNA, to commemorate the discovery.)

A newspaper headline on 15 May 1953 summed up the breakthrough with memorable economy: Why You Are You.

‘It’s great you can see the path down from the old Cavendish lab where he worked. Scientists are excitable people. What do you do when you’ve had this revelation? You go to the pub.’

tcd.ie/visitors

greeneking-pubs.co.uk/pubs/cambridgeshire/eagle

The discovery: DNA

The place: Trinity College, Dublin; The Eagle, Cambridge

After a pint of Eagle’s DNA you can stroll down King’s Parade towards another Trinity College. In the chapel there’s a statue of one of its alumni, Sir Isaac Newton; and in the college’s sublime library built by Sir Christopher Wren there is Newton’s hand-annotated copy of the book that changed the world: Principia Mathematica.

‘He was the first modern scientist. The Principia Mathematica of 1687 is the basis of all modern science. It has been replaced by Einstein’s theory of special relativity: but the key idea that the laws of nature that you encounter here on Earth are the same that govern the universe is made real in that document.

‘It was a big leap. The universal law of gravity in the same law that describes how a cannonball moves in relation to the Earth is the same one that dictates the Earth’s orbit around the sun. That’s Newton.’

The story goes that this particular realisation popped into Newton’s head – or onto it – when he was sitting under a tree and an apple fell from a branch above.

An hour’s drive north through eastern England and you come to the very place Newton was sitting when the apple fell on his head: a fine National Trust property called Woolsthorpe Manor and a budding scientist’s top Instagram opportunity.

nationaltrust.org.uk/woolsthorpe-manor

trinitycollegelibrarycambridge.wordpress.com/tag/principia-mathematica

The discovery: Space (sort of)

The place: Jodrell Bank Observatory, Macclesfield

You drive west for a couple of hours through the hills and the red brick Victorian buildings of the north Midlands towards the northwest of England. Then you reach some telescopes.

Not just any telescopes. This is the Jodrell Bank Observatory, a place that has been at the forefront of space exploration for seven decades.

‘I grew up in Manchester knowing about Jodrell Bank – my mum and dad would take me there. It is still one of the world’s largest radio telescopes and a very active research centre.’

The site is dominated by the Lovell radio telescope.

‘It’s unique. You feel this thing is capable of discovering places you can only dream of. It’s a symbol of everything that’s magical about astronomy.’

In its time, the Lovell (above) was the world’s largest telescope. Now the scientists at Jodrell Bank are devising the largest telescope array known to mankind, to be situated across Western Australia and parts of South Africa.

‘It is the headquarters of a new project to build the Square Kilometre Array. Jodrell is the premier research instrument. Even after 50 years it is still iconic.’

The discovery: The atomic nucleus; Graphene

The place: University of Manchester

Cox’s workplaces, when he’s not in front of a TV camera or in a 10,000-seater venue, include the Cern lab in Geneva – and the University of Manchester. For a physicist, this is no backwater. Ernest Rutherford discovered the atomic nucleus here. And graphene, the material that may well spark the next industrial revolution, was first isolated here in 2004 by Professors Andre Geim and Kostya Novoselov.

To say Cox is proud of his home city is a bit like saying Manchester United is a fairly popular football team.

‘The great physicist Freeman Dyson wrote a famous essay called Manchester and Athens – he said they are the two most important cities in the world. So you should go to them both. A friend of mine, [the designer] Peter Saville, also called Manchester “the first modern city”.

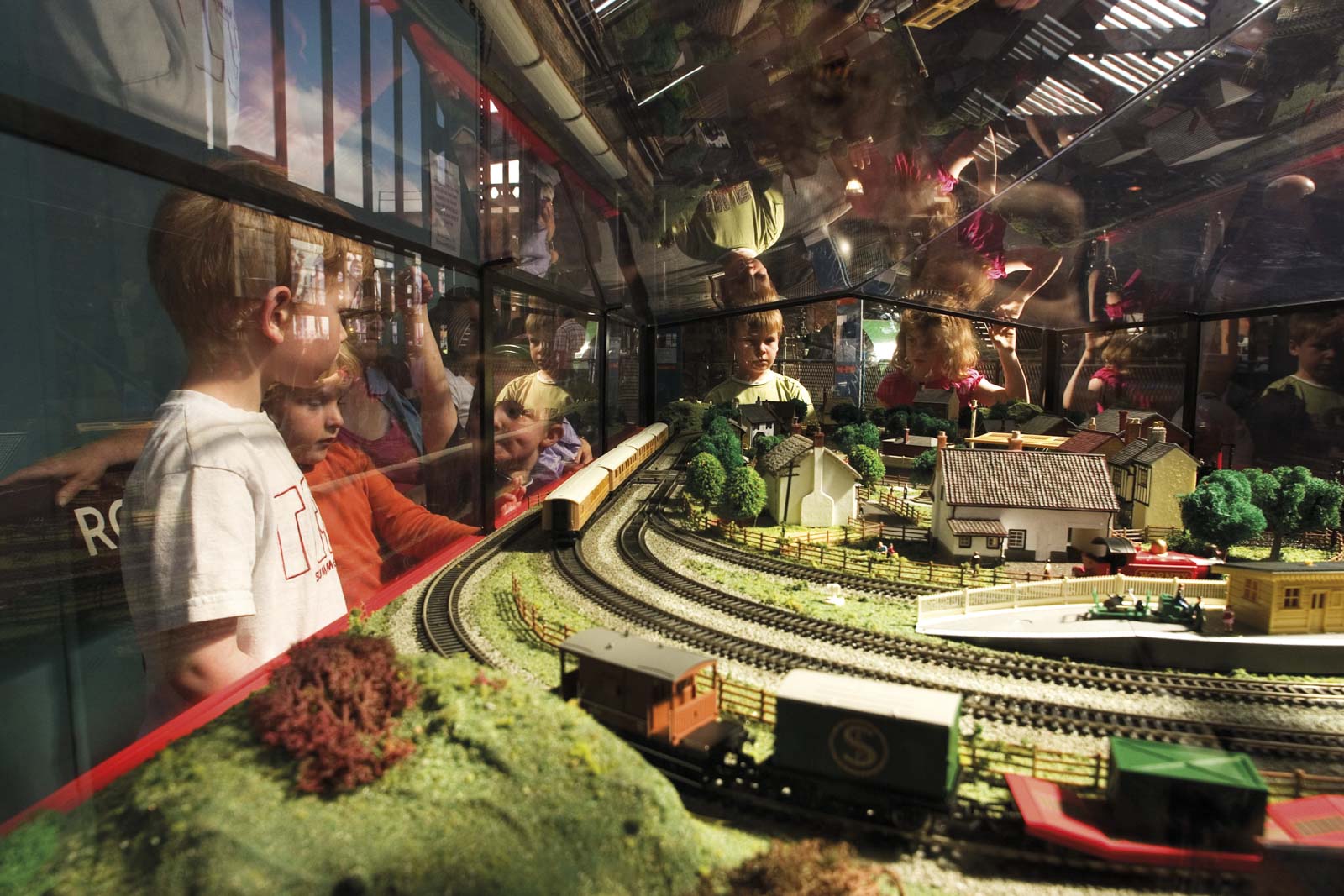

‘You can see why at Manchester’s Museum of Science and Industry. It’s terrific: you can see the industrial revolution beginning in that museum.

‘The first passenger railway station is also there – the museum was built on the Manchester to Liverpool line.

‘There’s a fascinating exhibition about the sewage system of Manchester. The city had one of the lowest life expectancies in the world. At the start of the industrial revolution it was just filthy. The Victorian engineers built this vast system of reservoirs and canals and completely transformed it. Water has always played a great part in civilisation.’

The water that flows down from the Pennine Hills above Manchester is exceptionally soft. As well as creating one of the other glories of northwest England – its bitter ale – it helped create the cotton trade, the world’s first large-scale manufacturing industry.

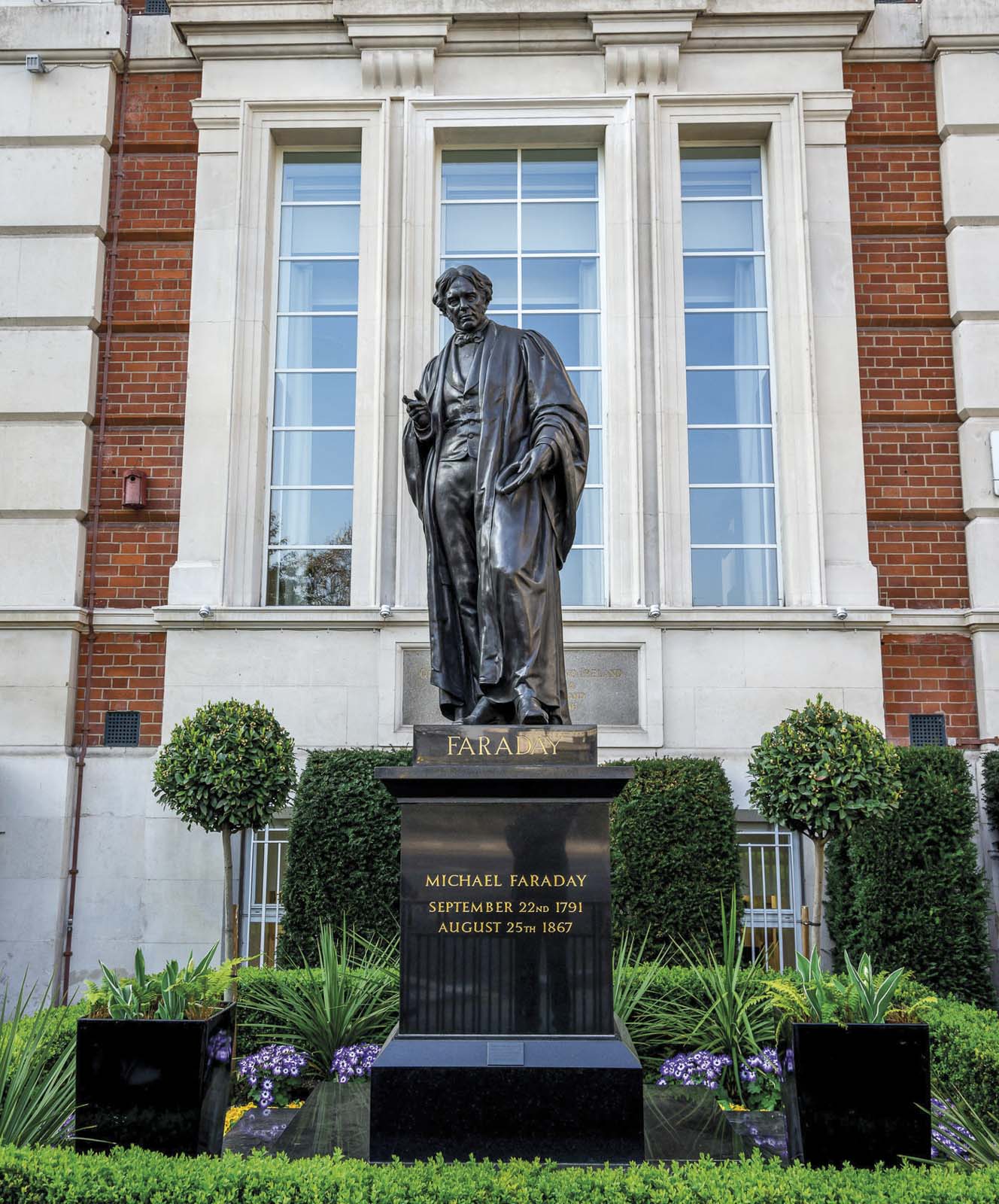

The discovery: Electromagnetism

The place: Royal Institution, London

Last year, Cox broke his own Guinness World Record for the most tickets sold for a science tour. He spent much of the year (as he will 2019) touring worldwide with his Brian Cox Live lectures.

He has a battery of wonderful technology at his disposal, including a 30 metre-wide LED screen. Yet he sees the shows simply as an evolution of the small-scale lectures that took place in the 19th century, which began to introduce scientific discovery to a wider public.

If you could send him back in time (and he’d know better than most how to do that) he’d go back to the Royal Institution lectures of the 1820s on Mayfair’s Albemarle Street.

‘The lecture theatre there is an important place for me. You are in one of those great places. It was where Michael Faraday and Joseph Banks spoke – men who really understood that science is not something to be kept to yourself.

‘And Faraday was himself discovered by Humphrey Davy when he went to his public lectures. Faraday was the son of a blacksmith. Inspired by the lectures, he wrote to Davey and said, “I want to be your assistant.”’

Faraday’s work led to the widescale application of electricity in industry, the home – and everywhere, in fact.

‘Faraday’s lab at the Royal Institution is where he laid the foundations of modern civilisation.

‘You can see it. It’s still there, that lab.’ rigb.org

Professor Brian Cox was in Hong Kong to promote the Great Festival of Innovation – Hong Kong, which will be held over 21-24 March at the Asia Society. events.trade.gov.uk/the-great-festival-of-innovation-hong-kong-2018

Cathay Pacific flies to London 42 times a week; to Manchester seven times a week; and launches a four-times-weekly service to Dublin from Hong Kong on 2 June