The East view: true thinkers choose their own place

Many city dwellers need an occasional break from the hustle and bustle. They find tranquillity in idyllic surroundings, unwinding perhaps at a camp site or in a remote farmhouse. Abundant nature and fresh air offer not just a holiday for the lungs, but also an escape that calms the weary soul. But few urbanites want to make the move permanent. The rustic way of life is wonderful – in short bursts. Over time, they get bored of being refreshed and relaxed.

In ancient China – and in China today, as we’ll see – rural-urban relocation was an emotional issue.

The civil service examination system had its beginnings in the Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD), when scholars were finally granted a path to political power through merit rather than patronage. The system tied in with regional quotas. Candidates from rural communities formed a unique farmer-scholar culture.

The difference between city and village had a political implication: the city was the centre of power and politics, a place where scholars strived to become part of the political elite. The ‘pure’ farmer ‘rises and works at sunrise, retires at sunset’, and is therefore ‘unaffected by the imperial power’ (Song of the Peasants). In short, it was the opposite of climbing the greasy pole: it was a hermit’s life.

The author held that a ‘serious hermit remains a human island in the city’. But a secluded place gave substance to the vow to abandon the pursuit of power. In reality, ancient scholars who retired to the country were often reluctant hermits – they had a hard time in the office and found no way out other than quitting it altogether. Others opted for a hermit’s life because they were disillusioned by corrupt bureaucracy.

This practice had its roots in Confucian teaching. ‘When the Way prevails in the world, show yourself. When it does not, then hide,’ he said (The Analects of Confucius). The best Confucian scholars should follow the example of the philosopher himself: ‘When it was proper to go away quickly, he did so; when it was proper to delay, he did so; when it was proper to keep in retirement, he did so; when it was proper to go into office, he did so.’ So said Mencius about the philosopher in The Works of Mencius.

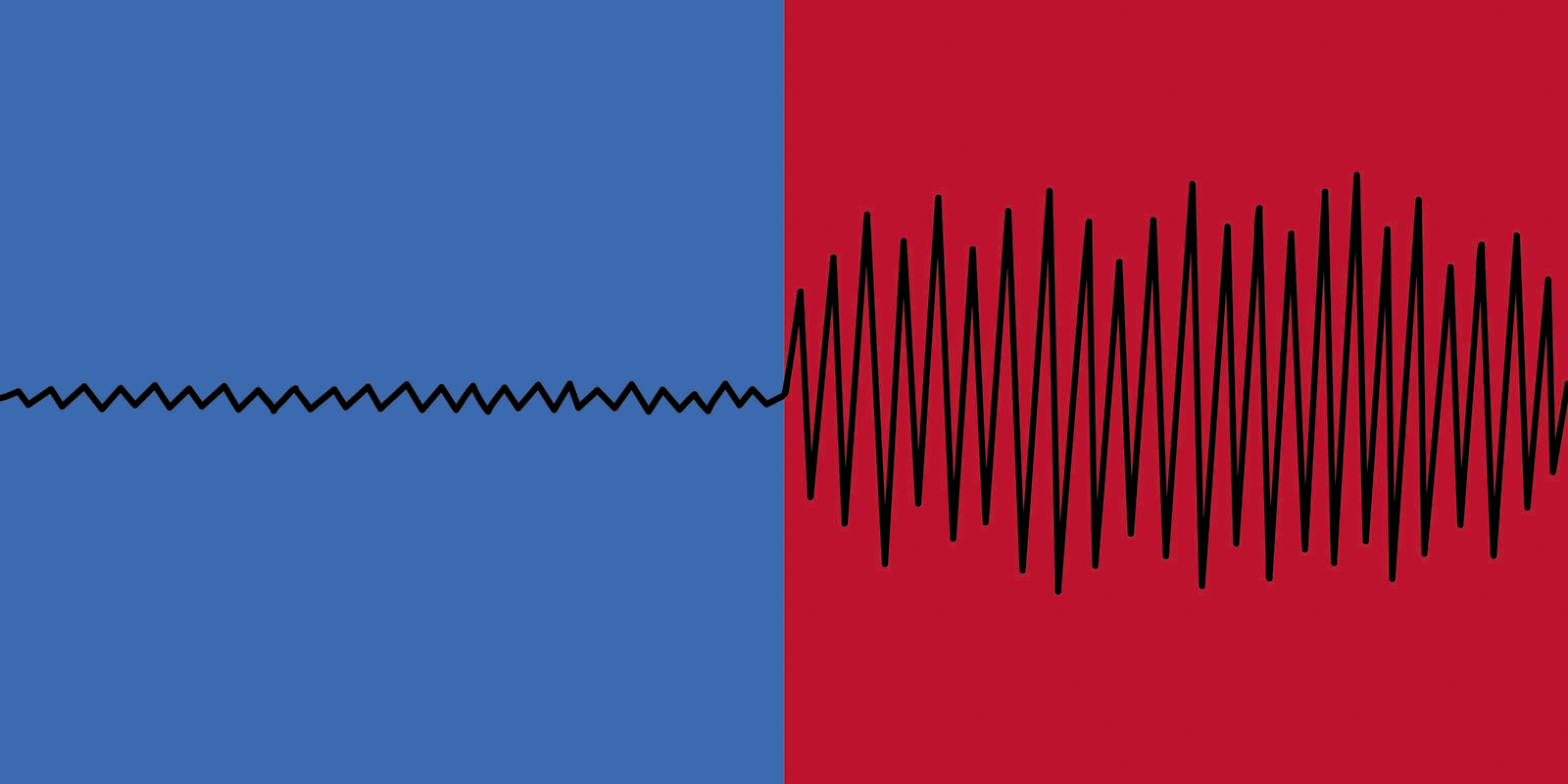

Perhaps the idea of living a hermit’s life is still present in modern Chinese intellectuals. But you can’t escape anywhere in a world where the line between the country and the city isn’t blurred by technology. Today, even the most determined to find complete seclusion can still connect to the outside world.

In Asia today, the traffic is overwhelmingly in the other direction as young people leave their villages and assimilate into urban life. ‘Coming from a rural area’ is all too often a label of discrimination.

Fan Yusu is a country-born writer who wrote I Am Fan Yusu, an autobiographical account that became an overnight sensation. She is a perfect example of such discrimination. A young girl from rural Hubei, she ends up as the nanny of a rich family in Beijing. She writes with a plain but subtle style. Many people are touched by her story told in a uniquely affecting way.

Yet people – urban people – still find fault in her writings and deride her prose style as ‘a bowl of coarse rice’. It’s a modern story with a very ancient lineage.

The West view: our urban values need to change

In 2014, the UN announced that for the first time more than half the world’s population lived in urban areas. By 2050, that will rise to two thirds. But although it has taken until the 21st century for the city to dominate the world, Western philosophy has been an urban phenomenon for millennia. The city has shaped the contours of its thought as surely as skyscrapers shape the modern skyline.

Western philosophy was born in Greece, growing up and living the prime of its life in Athens, the greatest city-state of its time. This almost certainly influenced the problems its philosophers chose to focus on, and the answers they gave to them.

When Aristotle considered the good life, for example, he had in mind a free man of Athens served by slaves, not a farmer in the Peloponnese struggling with nature. The best life, he concluded, was one of contemplation, a life only available to urban men like him. And when Plato imagined his ideal Republic, again the model was a relatively small city-state, not a sprawling empire or a thinly and sparsely populated nation.

In the era of modern philosophy, cities again became the focus. The Enlightenment flourished in Amsterdam, Paris and Edinburgh. These were centres of trade and exchange where people came from all corners of the known world. No wonder, then, that a conception of reason emerged that was universal and cosmopolitan, not rooted to particular times and places.

This seems so natural to Westerners that they don’t even notice it as a feature of their way of thinking. Their assumption that philosophy is about the universal and has nothing to say about place is not shared around the world, as I discovered when I went to last year’s East-West Philosophers Conference in Hawaii on the theme of ‘place’. There was plenty to be said, but not by scholars of Western philosophy, who were thin on the ground. (I got around the problem by talking about the absence of place in Western philosophy.)

East vs West: restaurants

One feature of urban life is that it is largely impersonal. You don’t know most of the people you pass every day and many you will never see again. It should not therefore be surprising that the West’s urban philosophical culture has generated a moral philosophy that is proudly impersonal. The clearest example of this is utilitarianism, which was built among the chimney stacks of Victorian England. In this system, the right thing to do is whatever benefits the greatest number, the wrong whatever diminishes its welfare. Your relationship to the people you harm or help is irrelevant. ‘Every man to count for one and no-one to count for more than one,’ as ‘Bentham’s dictum’, named after the founder of utilitarianism, puts it. It’s a motto that resonates less in a village, where the special treatment of kith and kin would be second nature.

Perhaps the most striking reflection of the urban bias of Western philosophy is the short shrift it generally gives to nature. The 17th century English philosopher Hobbes famously defined civilisation in contrast to the ‘state of nature’ which he saw as a war of all against all, red in tooth and claw, where life was ‘nasty, brutish and short’.

Hobbes’ hyperbole reflects a common prejudice of his profession. For philosophers, untamed nature is the antithesis of rational society. The primitive human feels at home in the wild but it requires the distance of the civilised thinker to understand it.

The most notable dissenter was Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who despised the Enlightenment Paris of his age. Although he did not, as is widely believed, advocate a return to the era of the ‘noble savage’ he did think that there was a purity and simplicity of existence before modern society forced us to live among ever larger groups, alienated from nature by our brick houses and cobbled streets.

Today, Rousseau’s lament seems more prescient than romantic. While cities are still adored for their energy and creativity, we have become more aware of the problems associated with living in them. Mental health problems are more common in cities than elsewhere. Inequality also tends to be higher where the rich locate their globally connected homes and the poor congregate to take the badly paid jobs required to service them, tourists and business travellers.

The city is here to stay. But perhaps philosophy can help us recover some of the values we left behind in the country and so make our urban environment more human and more humane. Communitarian thinkers like Michael Sandel and Michael Walzer have drawn our attention to the need to promote social solidarity by nurturing particular ties as well as abstract values. Advocates of ‘care ethics’ like Carol Gilligan have also emphasised the role of emotion and relationships in morality. Bureaucratic, anonymous urban values are at last being balanced with more organic, personal ones that the countryside never abandoned.