The East view: it’s not just a body

Wai-Hung Wong

Chinese medicine rolled out in flu fight,’ ran the front-page headline in Hong Kong newspaper The Standard in July. In the annual battle against the flu virus, the city’s Hospital Authority was sending patients (more than 27,000 of them between April and August) to Chinese medicine clinics. Among the suggested treatments for viruses spreading due to the hot, humid summer weather were boiling chrysanthemum, mint and beefsteak plants into a drink, and a new treatment that will ‘clear heat’ and ‘eliminate dampness’ in the body.

Today, Chinese medicine is still regarded as a legitimate choice, if not a necessity, in China, Hong Kong and other ethnic Chinese communities in Western cities. It is at least an alternative when Western medicine fails; and in the most extreme cases, it is the only option. While old systems of treating the body, such as the belief in the four humours, developed by the ancient Greeks, have long been replaced by modern medicine in the West, the endurance of ancient Chinese medicine in the East is an intriguing phenomenon to outsiders.

They assume that Chinese medicine is no more than an inherited suite of folk remedies and herbal cures that lack scientific support and efficacy. After all, Western folk remedies were abandoned because they were unreliable and unsystematic (see Julian’s piece). Their fate was sealed when modern medicine emerged, along with it a systemised structure – and much better outcomes.

These assumptions may not be completely wrong: yet they are also an oversimplification.

By definition, traditional Chinese medicine goes way beyond folk remedies. It is a medical system supported by arcane theories extended and developed over time. The substitution of folk remedies for modern Western medicine was an inevitable evolution. But for Western medicine to supersede its Chinese counterpart in the East, it will take a paradigm shift.

That’s not to say Chinese medicine is rock-solid. The Chinese version of Wikipedia, for example, has an entry for Movement for the Abolishment of Chinese Medicine, which calls for action against ‘unscientific and far less competent Chinese medicine’. The notion can be traced back to Yu Yue, a Qing dynasty scholar who launched a full assault against Chinese medicine practitioners in his text On Abolishing Chinese Medicine, saying it was pointless favouring doctors over shaman healers as there was no essential difference between the two. (He meant Chinese doctors in his attack.)

That Chinese medicine is unscientific is a direct criticism of its unproven, esoteric nature. Its theories remain untouchable by science nowadays. At best, science can gauge the therapeutic efficacy of a treatment or herb, but this alone cannot prove the validity of Chinese medicine. Even the idea of therapeutic efficacy is disputable: Chinese medicine judges efficacy differently from Western medics.

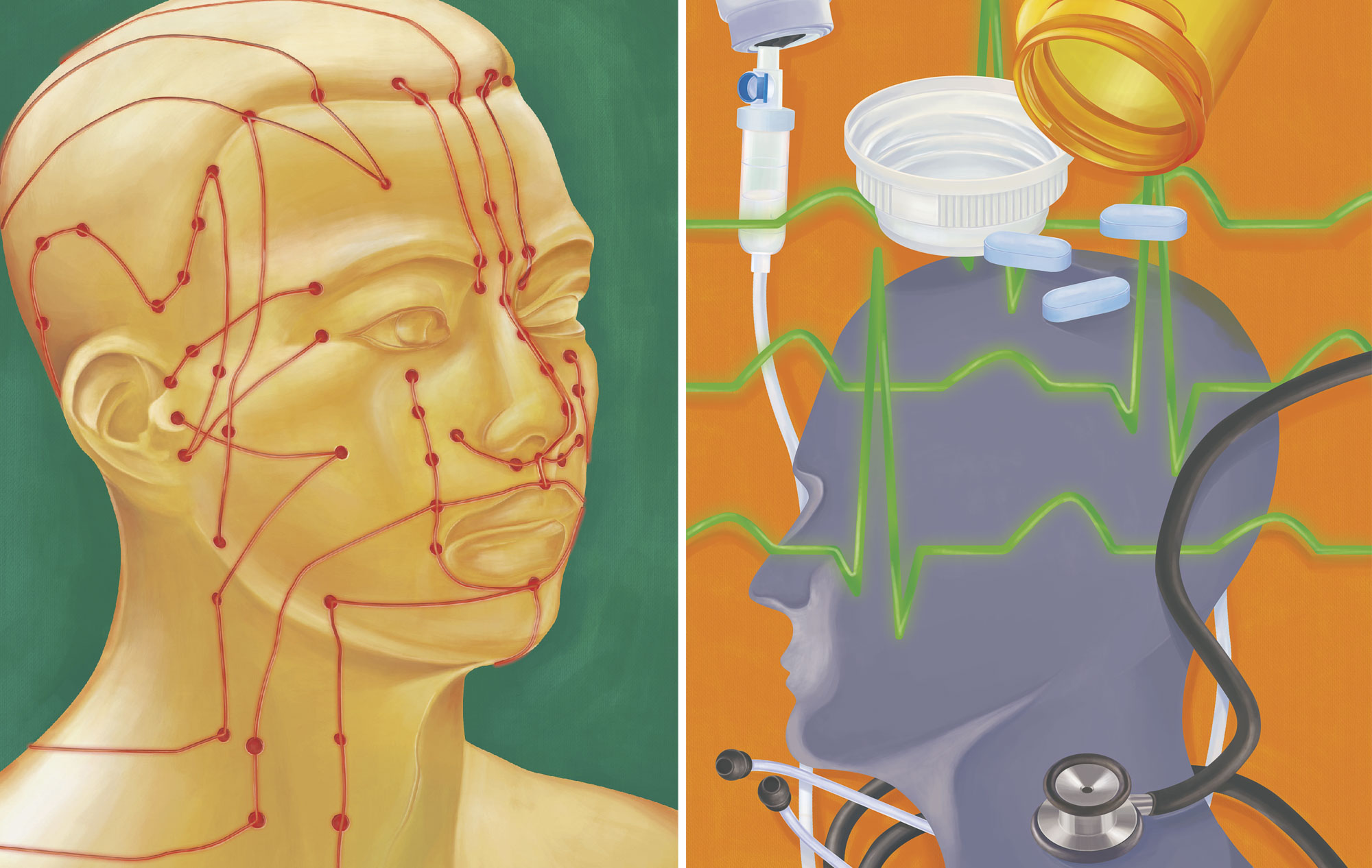

Chinese medicine takes a metaphysical view of the human body, whose constitution is dictated by the yin-yang balance and the five elements. Esoteric Scripture of the Yellow Emperor, the earliest Chinese medical text, concludes that ‘yin and yang are the principle of nature, the order of all beings, the source of change, the origin of life and death, and the realm of the gods. To cure a disease, one must seek its roots.’

The Chinese belief in energy channels and qi (energy flow) has been rejected outright by Western medicine. The Western idea of the human body is strictly biological.

To criticise the esoteric traits of Chinese medicine is to criticise its metaphysical basis. Western civilisation and philosophy certainly has a fair share of metaphysics that concerns non-physical entities such as the soul, but it has long since been divorced from modern medicine, which is considered a branch of natural science. Even if the doctor who treats you believes in the soul, he or she will only tend to your physical body. You would have to turn to a priest or pastor to heal the wounded soul.

The combination of Chinese and Western medical sciences, as proposed by some, can only be a superficial one – one that concerns the cures but not the theories. If Western medicine is to incorporate the metaphysical understandings of Chinese medicine, it will lose its scientific stance; and if Chinese medicine hacks off its metaphysical roots, as Yu Yue would have it, what remains will be a mere existence of traditional cures – Chinese medicine without its soul.

East vs. West: Expressing an opinion

The west view: it is just a body

Julian Baggini

In Britain, where I live, I’m always coming across places that offer traditional Chinese medicine. However, I have yet to see a single premises with ‘traditional Western medicine’ above the shop window.

If we ask why traditional medicine thrives outside the West but not in it, one obvious answer is that older forms of medicine only thrive in the absence of well-funded, widely available ‘proper’ medicine, when people seek help from whichever source they can, effective or not.

There may be more to this than advocates of traditional medicines would care to admit, but filling a gap left by an underfunded health service cannot be the whole story. Plenty of people seek help from ‘alternative medicine’ and many claim to find it. But most of that medicine is either old and foreign, like acupuncture and Ayurveda, or a relatively recent Western invention.

Homoeopathy, for example, was created in 1796, with one of its most popular schools, Bach flower remedies, founded in the 1930s. Chiropractic has its origins in the 1890s, while osteopathy was born in the United States in 1874. The only traditional Western medicine still practised to any degree is herbalism, and even that now draws on non-Western sources.

A fuller explanation requires an understanding of how the Western mind has shaped its medicine. One root is a dualism of mind and body that has characterised philosophy in the West since the time of Plato. For him, our souls ‘are simply fastened and glued to their bodies…only able to view existence through the bars of a prison’. Our bodies are merely temporary vessels to carry our true selves, our souls.

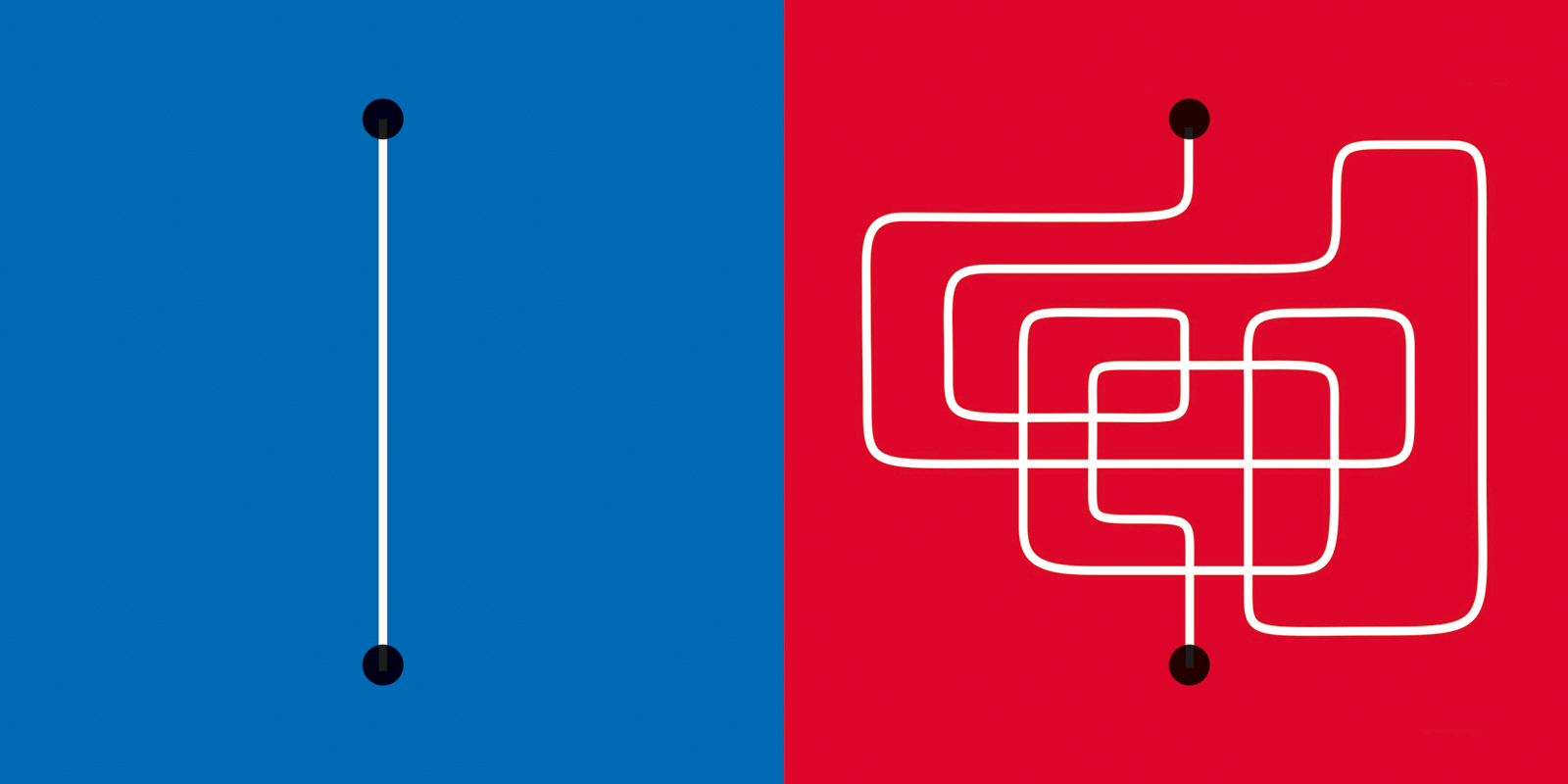

Not every philosopher has been as sharply dualistic as Plato; but he set the tone of thinking to come. One result is that medicine has been seen merely as an engineering problem. It does not require a holistic system of thought that brings together body and mind. All you need to know is which part to fix and you can be sent on your way, cured.

Only recently has mainstream medicine embraced the idea that to treat the whole patient you need to address emotional as well as physical needs; and that the body heals quicker when the mind is treated at the same time.

The mechanistic way of thinking is accentuated by another characteristic of Western philosophy: its reductionism. This is the method of understanding things by breaking them down to their smallest constituent parts. This is described clearly in the Encyclopédie, the French Enlightenment’s distillation of all secular knowledge. In its introduction, D’Alembert points out that ‘bodies have a large number of properties’ and that ‘in order to study each of them more thoroughly, we are obliged to consider them separately’.

This is an advantage, not an inconvenience. ‘This reduction,’ he wrote, ‘makes them easier to understand.’

Once again, the implications for medicine are clear. The body has a number of parts and properties and the way to understand them is to examine each one in isolation. Everyone knows that the body is a complete system but it is analysed and treated in terms of its parts.

A third, vital feature of Western philosophy is its strong idea of progress. Many attribute this to the Christian worldview that sees human history as moving in discrete phases, from the election of the Jews as the chosen people, through the times of prophets, to the coming of Christ, culminating in his return and the final judgement.

In many other times and places, however, time has been seen as more cyclical and history has no final destination, humanity no ultimate goal.

Stripped of its religious roots, belief in progress has become one of the defining features of Western thought since the Enlightenment. This leads to the wholesale shedding of old ideas as soon as newer, apparently better ones come along. Hence scientific medicine had no philosophical interest in preserving what worked from its folksy predecessors. Like so many beautiful buildings that were torn down to make way for forward-looking modern constructions, old medical practices simply had to go.

Belatedly, there is recognition that at least some forms of traditional medicine might have their merits after all. Most remarkable is the revival of interest in medical leeches. These little blood-sucking creatures have become a comic shorthand for all that was crude and ineffective in pre-modern medicine. But they did have some genuine benefits and now they are making a comeback. For example, they have been very effective in preventing tissue death after limb transplantation.

Belief in progress and scientific reductionism helped the West outpace the rest of the world for several centuries. But it also blinded it to resources in its own past. Traditional Western medicine looks unlikely to make a wholesale comeback but medicine is now adding older and holistic tools to its impressive modern technological kit.