Walk around any city in Asia and you’ll see people in English football shirts: Arsenal, Liverpool, Chelsea – all with the name of the wearer’s favourite player on the back.

You won’t see many Racing Club de Blackheath replica jerseys.

It’s partly a question of recognition – what is the Racing Club de Blackheath? – and partly one of quality. Made of low-tech, unbreathable South London cotton, after one wash the Blackheath shirt usually becomes a shapeless mess. Over the years they have been washed in rivers, mountain pools and zero-star-hotel sinks.

Still, there were plenty on show in Yangon’s East Hotel on the morning I got there. There was Chris in the 2001 Cuba tour version, Foster in the 2004 Pakistan. I had my classic Slovenia and Croatia 10th anniversary top. Now we had our new Myanmar tour shirts.

I’m tempted to say the bodies underneath match the quality of the outer garment. Even if a percentage of those middle-aged bodies have retained shapes dimly recognisable as the same ones that stepped onto the pitches of Poland in 1989 or Russia in 1993, the internal workings have taken an inevitable hammering. Among the players showing up for duty at the East Hotel, we counted one liver transplant, a recent heart operation and a captain prone to blackouts. That’s before you get onto the physiotherapy situation. Until Lebanon 1999, I was injury-free. The Achilles tendon injured on that tour was soon followed by calf muscles, knees, groin, lower back and adductor muscles.

Back to the question. What is the Racing Club de Blackheath?

We are a football team from the London ‘village’ of that name. Even in our younger days, we weren’t very good. But we have something special. While Barcelona has tika-taka and Liverpool the gegenpress, we have our own trademark: pioneering international diplomacy.

The annual Blackheath tour has a basic rule: favour destinations that have just undergone or might be about to go through profound political or social upheaval.

So we were in Poland in the year communism collapsed. We toured Eastern Europe as the former Soviet states gained their freedom. With a new century and a changed international landscape, we ventured to Lebanon, Cuba, Iran, Pakistan and Uzbekistan. We toured Syria at a time when, briefly, it looked as if the country would emerge from repression and dictatorship.

As a theory of travel it is beautifully simple. Ignore politics and social differences, past wars and current tensions: football is a bond. We get our games through embassies, football associations, hearsay. There have been epic mismatches, such as the time we took on a team of Iranian ex-internationals or the game against the Latvian third division champions. Actually, we beat the Latvians. They’re still wondering how we did it without touching the ball.

Now, like President Obama’s foreign policy, we’ve been pivoting to the East. After tours to Central Asia (Uzbekistan) and the Himalayas (Nepal) the time had come to capitalise on English football’s huge popularity further east. Myanmar looked like a good choice.

So there we were in Yangon, after a morning’s desultory sightseeing (no one does desultory better) in the Rangoon Tea House, described by Lonely Planet as a ‘stylishly designed hipster’ place. We were neither stylishly designed, nor hipster, but they found us a table and we tucked into samosas, bao and other things that do not form part of the modern footballer’s scientifically designed nutrition programme.

It was a chance to compare hats. Hats, the cheaper and sillier the better, are as important a part of the Blackheath armoury as the terrible football shirts. Steve, the tour chronicler and midfield genius (anyone who can pass the ball 10 metres in a straight line is a midfield genius for us), had managed to locate a cheap bamboo pith helmet of the kind favoured by British colonial administrators in the days when Myanmar – then called Burma – was part of the British Empire.

No one objected, other than on fashion grounds. The same went for our visit to Yangon’s magnificent Shwedagon Pagoda. The British rulers showed their disdain for local religious sensitivities by refusing to remove their shoes when entering the pagoda. We did. It’s possible some people wished we hadn’t.

The team went milling about somewhere, while I checked into a more prepossessing reminder of British rule, the old Governor’s Residence – now transformed into an elegant, shaded, hospitable and very un-Blackheath-like five-star hotel run by hotel group Belmond. My friends Lara and Gav took me to Rau Ram, a cool bar and restaurant that’s very much at the forefront of revitalised Yangon. If the city is to undergo the kind of transformation that the likes of Hanoi and Phnom Penh have been through, then Rau Ram points the way.

But let’s also hope that the architectural legacy of the former Rangoon doesn’t get swept away in the tourism and moneymaking frenzy.

I’ve seen plenty of towns – Tallinn (Estonia), Budapest (Hungary), Riga (Latvia), Tbilisi (Georgia), Baku (Azerbaijan) – go from run-down and atmospheric to glitzed-up in the years after a Blackheath tour. If we had an ounce of entrepreneurial zeal we’d have bought property in all the places we’d visited. An apartment in Prague at 1991 prices? We’d be multimillionaires. We could afford proper football shirts.

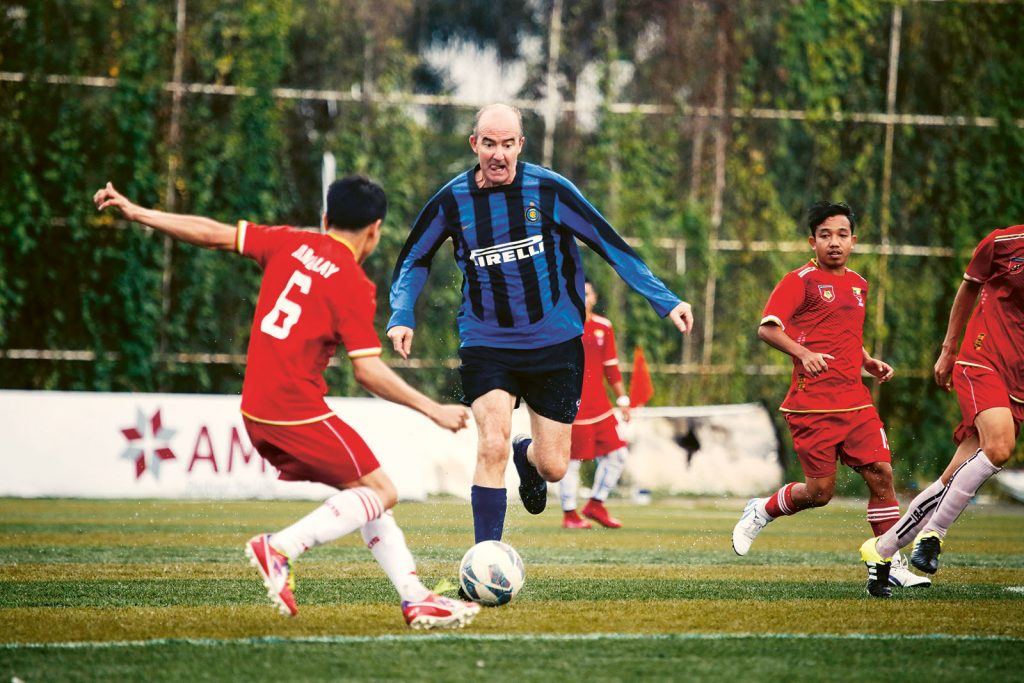

So to football. The Yangon United football pitch wasn’t the worst we’d played on (Nepal – crater running seven metres into the pitch from the touchline) or the best (Azerbaijan’s national stadium), but it was the wettest. The monsoon rain puddles slowed down the opposition, who only beat us 4-2. My hamstring went just before half time.

The next days saw more milling and mustering in airports and hotel lobbies as we travelled to Bagan and Inle Lake and cruised on the Irrawaddy River. It was the end of the rainy season. In a closely fought contest, the sun won the Southeast Asia Tropospheric Tournament. But it’s Myanmar: the storm clouds are never far away.

This is the standard tourist itinerary: but only the most grim-faced off-the-beaten-tracker would be anything but swept away by the places we saw.

Bagan – a landscape of 2,000-plus temples dotted around the plains on the Mandalay side of the Irrawaddy – inevitably gets compared to Angkor Wat. We set off to see the temples at dusk, squashing through the fields in light pony carts, some teammates unkindly comparing the ponies’ perky little trot to the running style that has given me so many muscular-skeletal issues over the years.

The 11th century Shwesandaw Pagoda is currently where everyone congregates to see the sunset and survey one of southern Asia’s more majestic scenes. Everyone was allowed to clamber up the fragile brick terraces to take their photographs: until the ban on tourists setting foot on these ancient monuments was recently reimposed. In this emerging economy, the interests of conservationists, tourism operators and the Ministry of Culture struggle to gain the upper hand. It’s currently 2-1 to the culture lobby.

Fewer tourists opt to view the temples from the Nyaung U Playground. But if you are more used to playing your football matches with a backdrop of London train tracks and tower blocks, even a couple of minor, crumbling stupas make for an impossibly romantic view beyond the touchline.

Homemade banners and flags advertised the Friendship Football Match against SMC GG Eleven, which, true to that friendly spirit, we lost.

At this point – and there is usually a point like this on tour – we began to be concerned that friendship was all very well, but prestige was at stake. We needed to win the last game.

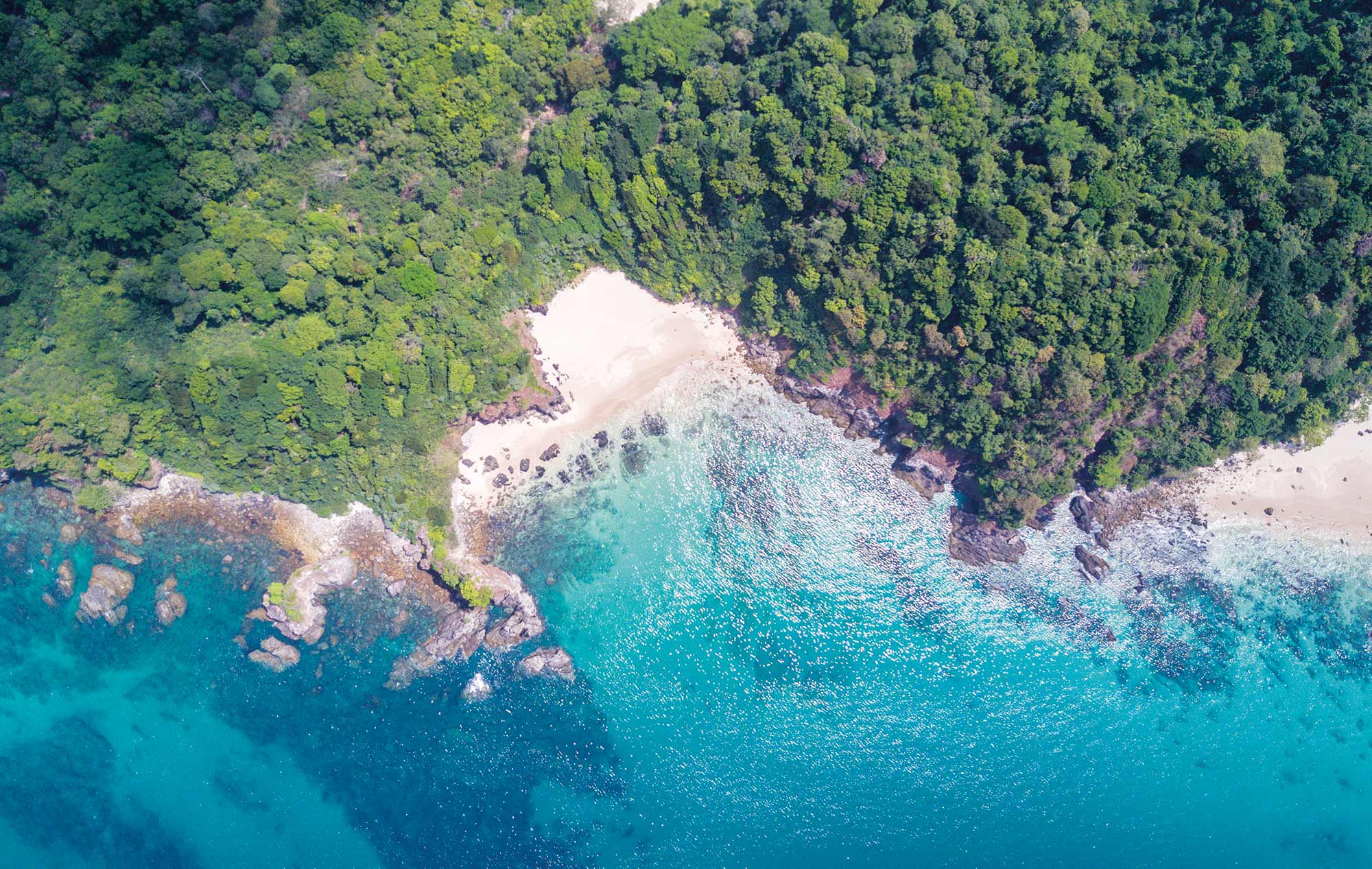

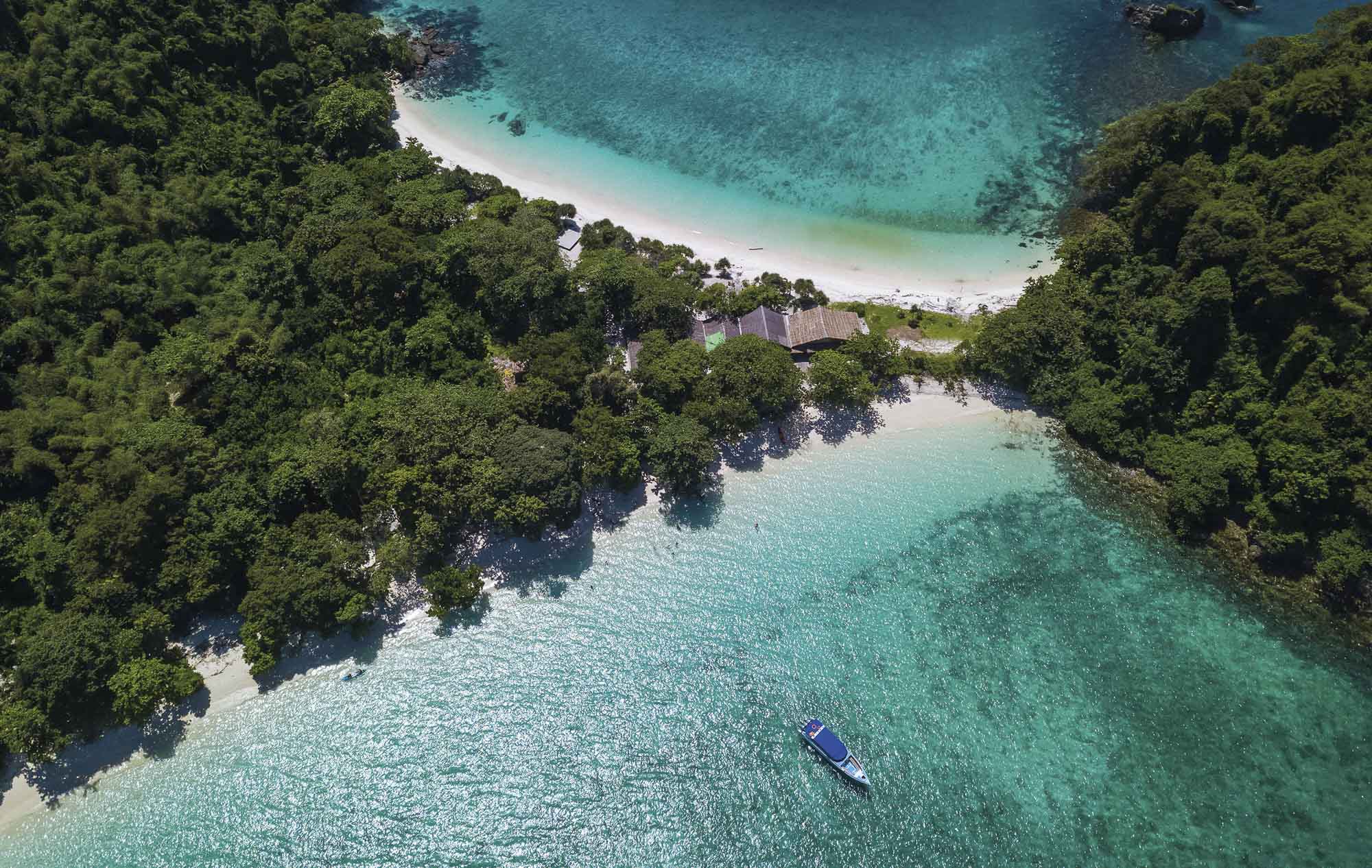

But preparations, again, were not what you’ll find in a Fifa coaching manual. We found ourselves in a pleasant riverside hotel on Inle Lake, talking tactics over Myanmar beers until early in the morning. The next day we went out on a flotilla of long, low boats for a big lunch and to see the lake villages. The rain beat down, then the sun. My dodgy legs turned a colonial pink.

Tourism has brought people to the stilted bamboo villages, to buy silks and silver and to sample the spicy Inle cuisine. Like all settlements on the water, you find yourself marvelling at the sheer ingenuity of life here, every village a rudimentary Venice of walkways, bridges and floating gardens. Most ingenious of all is the way the fishermen negotiate their way through the reed-filled channels, one leg wrapped around the oar, the other tiptoe on the prow. I didn’t try it. My physiotherapist would have kittens.

But I was just about mobile enough for the last game in the regional capital of Taunggyi: off the main tourist map, and all the more welcoming for it. This was the single most moving and noisy reception we’d ever had on tour. Drums were pounded, cymbals clashed, plastic banners reading Welcome Racing Old Stars Club displayed, and complaints that we were an hour late for the match unmade.

And, finally, we won. It was getting pretty dark by the time I managed to scoop the ball over the goalkeeper for our final goal. My various ligaments and joints strained, but stayed intact. The final whistle blew. We partied on the pitch in the dusk and everyone hugged everyone else. No one asked where David Beckham was. A little bit of a new bridge had been built.

Need to know

Belmond Governor’s Residence, Yangon

Elegant 1920s teak villa set among lotus ponds, lawns and gardens.

belmond.com

Zfreeti Hotel, Bagan

Pleasant, modernised-trad place with easy access to Nyaung U Bagan’s busy restaurant scene. zfreeti.com

Thanaka Hotel, Inle

Airy, simply furnished rooms and a fine riverside location.

thanakha-inle-hotel.com

For more on the Racing Club de Blackheath’s tours, go to rcdeb.com