There are two roads that run north from Perth to Shark Bay in Western Australia. State Route 60 stays within boomerang-throwing distance of the ocean. Highway 1 heads inland, with farmland and scrubby bush around you and, to your right, lots of empty red nothing. You’ve got over 800 kilometres ahead, but there’s no point in going fast – even if the retired Australians, taking it nice and slow touring the land in their motorhomes and caravans, would let you.

You’ve also got 350 million years of the Earth’s history to cover. You’re going to see the origin of life and the founding of Australia, as well some of the most extraordinary natural features on the planet. You can’t rush these things.

Actually, you can go even further back, much, much further back if you venture inland. I’d always thought the world’s oldest rocks were in Greenland or Scotland. But they’re here in Western Australia in the Jack Hills. Zircon crystals discovered embedded in its rocks date back 4.39 billion years: and that’s almost as old as the Earth itself.

But you’ll need proper scientific gear to appreciate the Jack Hills scenery. So best to stick to Highway 1 and make your first stop a visit to some rocks that you can capture on Instagram without a scanning electron microscope.

The Pinnacles in the Nambung National Park are limestone towers sitting out in the yellow sand like several thousand petrified wizards’ hats. It’s a seriously strange landscape.

To work out how this place came to be, imagine making a small pile of shells on a beach. The sea recedes, the beach becomes dry semi-desert, the wind blows away the sand and your little collection of shells grows tall and calcifies. You come back 10,000 years later and you’ve got a pinnacle.

The Pinnacles are ultra-contemporary structures – 30,000 years old at most. Practically yesterday. But before we really get ancient, we need to sample another of this coastline’s riches – western rock lobsters. So it’s lunch at the Lobster Shack in the town of Cervantes, before turning off the road and heading to Lake Thetis to visit the relatives.

These relatives of ours are flat, undistinguished shapes that lie in the shallow waters of the lake. I have a colleague who has a strange aversion to rocks. I can hear her saying, ‘So you’re saying we all descended from those things? Great. Where’s the bar?’

‘Those’ are not rocks, but thrombolites (you can see their taller relations, stromatolites, further up the coast in Hamelin Pool). Looking at them in the warm afternoon sunshine made me shiver. Collections of cyanobacteria like these were some of the very first life forms to exist on the planet. The thrombolites of Lake Thetis are descendants of our most ancient descendants. Be grateful: like all good parents they left us with a very useful legacy – oxygen. (And germs. There are around 3,000 bacteria crowded into a square metre. At which point anyone visiting from Hong Kong will say: yep – definitely our ancestors.)

That was 3.5 billion years ago. Let’s leave the thrombolites to stew gently for a few more million years while more complex organisms begin to appear – little cockles that die and leave their shells lying around. Multiply a few trillion cockles by several million years and you get Shell Beach.

You know how the story goes. Eventually, life gets bored lounging around in the sea, grows a pair (of lungs) and ventures onto land.

Here’s one of them. We’ve dipped south towards the ocean road and turned off into the Kalbarri National Park. We are standing 200 metres above a river valley that cuts deep through the soft red rock. It’s as if someone has said, ‘Let’s make the Grand Canyon, but we’ll do it a bit lower and more Australian.’ Sure enough, way down below, a kangaroo hops out from the shade of a gum tree for an early supper.

But it’s an older creature we’re looking at up here. Again, I hear my colleague (the rock critic) saying, ‘That looks like a tyre track.’ Look more closely and you see the fossilised indentation of a tail. Once, this vertiginous rock was a beach and that tail belonged to some kind of scorpion. A very, very old scorpion.

It’s dry, dry, dry and hot, hot, hot up here, even in midwinter. Things get preserved. The wind blows red dust, water evaporates, leaving saltpans and hypersaline pools by glittering turquoise seas.

Time passes. Creatures adapt. Around 420 million years ago, sharks appear. The 40 or so swimming around us as we wade out into, yes, Shark Bay, are a little less intimidating than their ancestors, the fearsome Megalodon. In fact, these little fellas, around a metre long at most, are known as nervous sharks. Sure enough, they catch a glimpse of my white English legs and, perhaps understandably, skitter off at speed. Steve Irwin this isn’t. But as a way to pass a sunny morning, paddling with nervous sharks is definitely one of the more therapeutic.

To plan your own road trip, visit this site for Hertz rental car promotions.

More time passes. Dolphins emerge around 48 million years ago – as they still do, every day, like clockwork, at Monkey Mia, a few kilometres north. A gaping gaggle of tourists watches as the pod of females float in like starlets in front of a premiere-night crowd. The cameras click, the dolphins roll over and wave a gracious flipper, then get given more fish.

The day before yesterday, 65,000 years ago, another animal appeared: ‘my mob’, as Darren ‘Capes’ Capewell calls his aboriginal forebears.

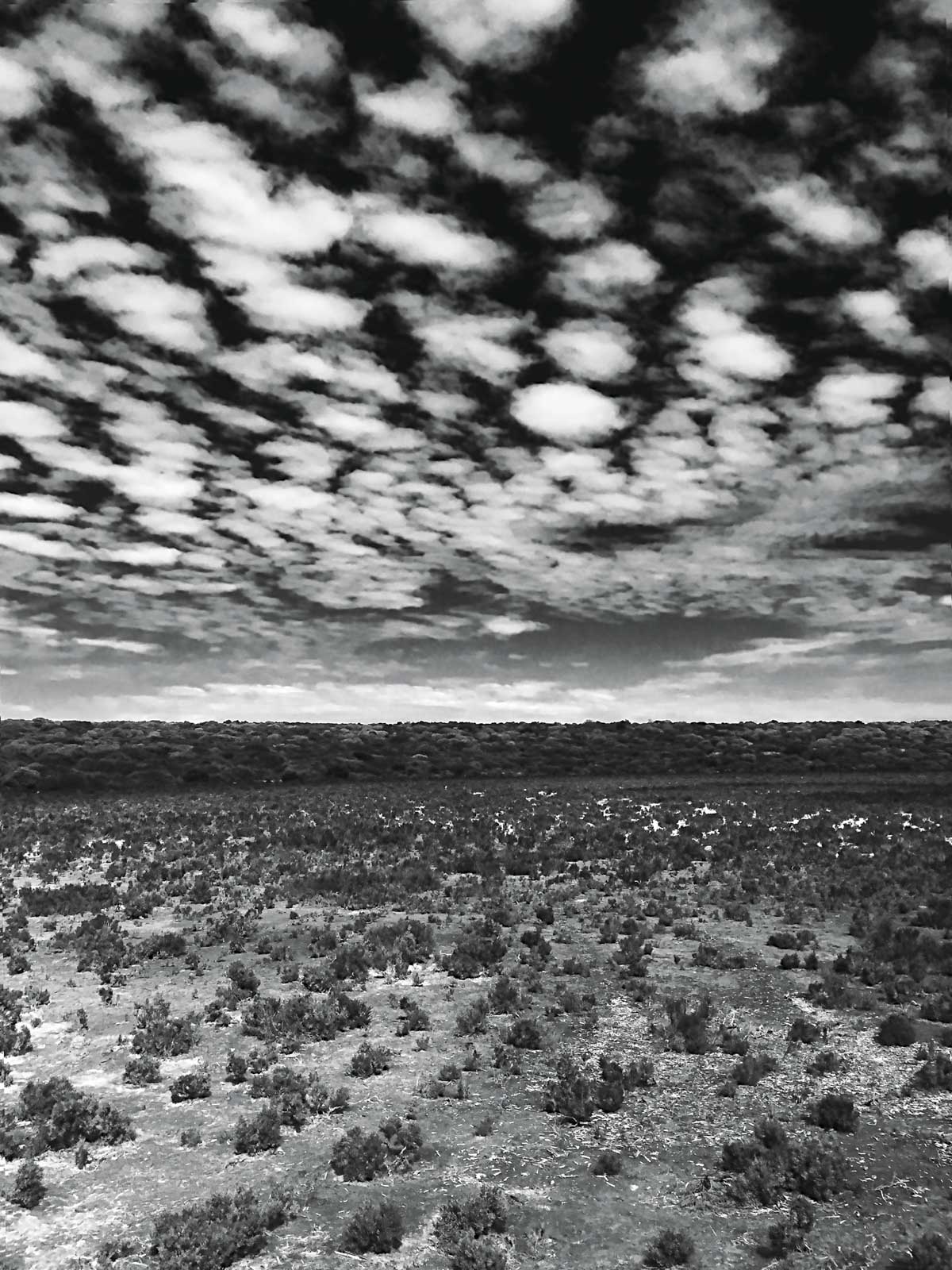

Capes’ ancestors proved much more adaptable to this harsh place than the Europeans that followed, many, many generations later. We are in the François Peron National Park, 52,500 hectares of shrublands and sandplains. Not harsh to Capes, mind: it’s a larder. We spend a day fossicking around the bush, paddling around the Big Lagoon in kayaks as rays and turtles dart around us. Capes stands in the shallows and traps a ray like a farmer at a sheep dip, holding up its strange, feminine-alien moonface up in the light before letting it scoot off. We end the day in a waterhole – actually, a hot pool thoughtfully provided for dusty, salty visitors outside the old homestead near the entrance to the lagoon.

François Peron, a late 18th century French explorer, certainly wasn’t the first European that we know set foot in Australia; nor was Captain James Cook. That honour goes to a little known Dutch sea captain called Dirk Hartog.

He was not one of the great explorers. Hartog was more like one of those successful business travellers you see around you on the plane today. As an employee of the first great multinational, the Dutch East India Company, he spent his time commuting between Amsterdam and offices in Batavia (modern day Jakarta), doing deals, transporting goods and probably getting very drunk with the other expats. Times were good. The Dutch had a secret weapon over their rivals: they’d found a way of sailing far south and catching the Roaring Forties. It’s a bit like when the captain tells you the good news that we’ve picked up a nice tail wind. ‘We’re happy to inform passengers that we will be plundering Asia a full two decades in advance of the British fleet.’

But these were the days before longitude (or rather, the discovery of longitude: longitude was always there). Miscalculate your run up the Indian Ocean and you bash into Australia. That’s precisely what happened to Hartog’s ship, the Eendracht.

The long, thin island he bashed into didn’t impress him much. He was impatient to be in the markets of Batavia haggling over spices, not gazing over an endless expanse of spinifex grasses or standing on the dunes trying to get a glimpse of a humpback whale.

But unlike other merchants who may have set foot on Australian soil before him, Hartog paused long enough to leave a pewter plate saying, more or less, Dirk Was Here. In short, he left evidence.

That was in October 1616. You may have seen the 400th anniversary events on Dirk Hartog Island covered in the international media. This useless place, this unwelcome stopover, turned out to be the thing that immortalised his name.

And 1616, in terms of the journey in time we have taken up Western Australia’s Coral Coast, really was five minutes ago. The fishermen, the guano collectors, the gold hunters and sheep farmers all came here to scratch a living and build their little towns. Today, the big money is inland and underground in the mines and the kind of geology that makes rather more money than tourists paying a few bucks to see the Pinnacles or Kalbarri. The coast doesn’t have the infrastructure of the east – no casinos, starry hotels, luxury resorts, Michelin-starred restaurants or funky boutiques. You’re in the land of plain motels, crazy pubs, huge steaks and big beards that were big even before hipsters made them big. And it’s an absolute blast.