The landscape was light industrial meets post-economic meltdown. There was an African haze over everything as dense as the gloom that’s enveloped Greece since the 2008 financial crisis. The wind was in from the Sahara and Mount Olympus was almost invisible through the dust particles. The gods were hiding.

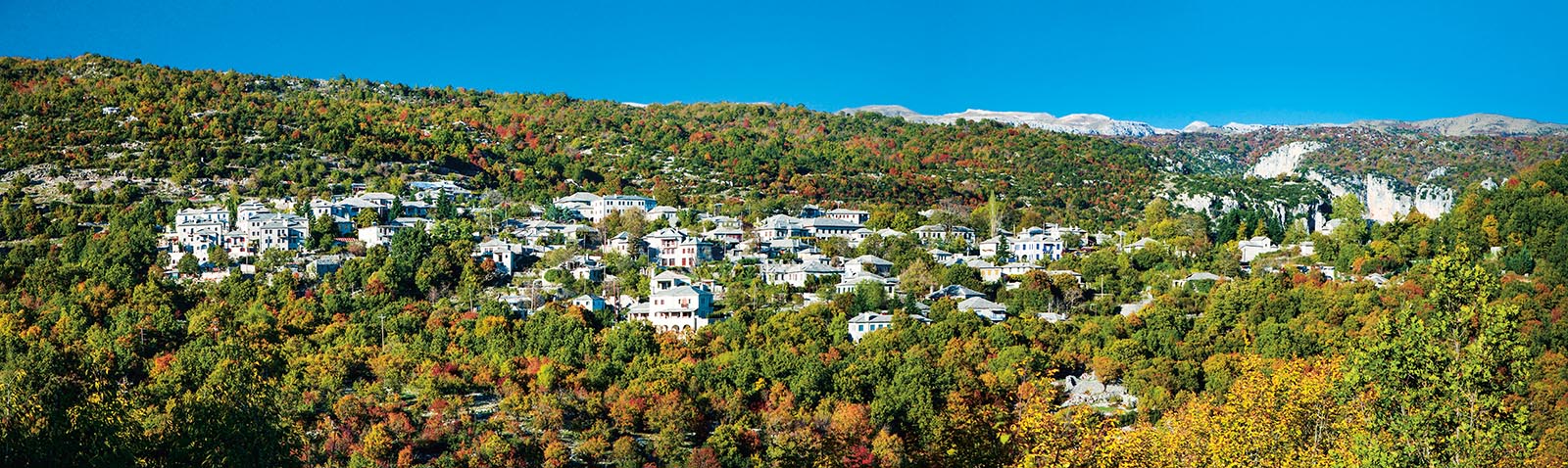

We were driving west from the northern Greek city of Thessaloniki to the Epirus region of northwestern Greece. After a couple of hours, we drove through a long tunnel under the Pindus mountain range. The road thinned and climbed. The dust clouds cleared. And so we found ourselves in the Zagori.

The word means ‘the land behind the mountains’. After the scratchiness and dust of the plains, the meadows and hillsides were thick with Sweet William, poppies and camomile, wild garlic and strawberries, fig and juniper.

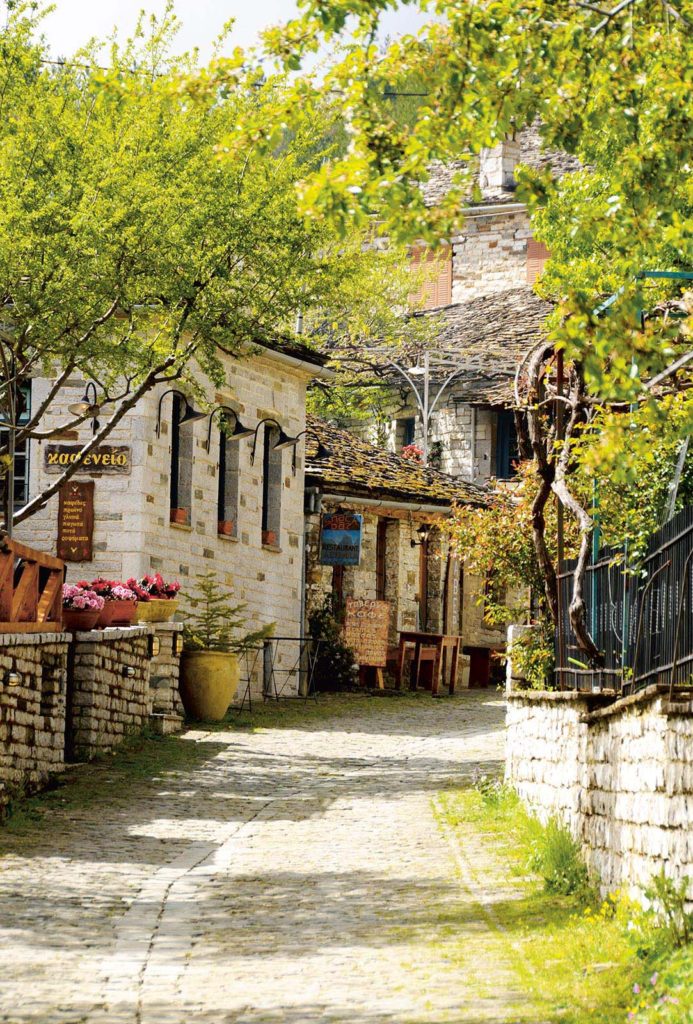

We reached Mesovouni, the first Zagori village proper. It was an immaculate place of handsome stone houses, freshly swept pavements, healthy cypress trees and prosperous-looking restaurants.

Further up the mountain road we stopped at another box-fresh, picture-perfect village: Aristi, and the Aristi Mountain Resort. The light-coloured stones on the cobbled paths looked as if they had been individually cared for. Yet this was not some model village straight off an architect’s computer. It has been here in its present form since at least the 1700s. I expected to find agricultural villages clinging untidily to a precarious living. Instead, we could have been visiting an inland town of the Côte d’Azur or a hilltop retreat in Tuscany.

So what was the story here?

The Zagorians were once rich. They made their fortunes between the 14th and 19th centuries. Far from the influence of Athens, they made their peace with the Ottoman Empire and secured their autonomy – the area’s mountains and gorges were simply too much trouble for the Turks to occupy.

Zagori merchants set up lucrative trade routes to the Balkans and beyond, to Vienna, Bucharest and Constantinople. You see their wealth in their fine stone village houses and, above all, in the bridges.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Zagori bridge-builders were among the finest and most technologically advanced in the world. They kept their engineering secrets to themselves and travelled far and wide. But they built many bridges at home, too. At Aoös, Tsipiana, Kokoro and dozens more places you see these beautiful marvels of engineering set against the heartbreaking backdrop of fast-flowing, crystal-clear, pebbly rivers and snow-capped peaks.

It was maybe the mountain air that made me a little lightheaded, but standing on the Kalogeriko bridge near Kipi I scribbled this in my notebook: ‘When the time comes for my ashes to be scattered, I think this will be the spot to do it. No hurry.’

But in the 20th century this land of milk and honey dried up. For the Greeks it became synonymous with rural desolation; and desperate heroism.

With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Zagori lost its markets and its purpose. Worse was to come when the Second World War broke out. The Italians invaded from Albania. The Greek forces mobilised in the Zagori and forced the Italians back deep into Albanian territory. Their heroic victory in the Battle of Elaia-Kalamas was the sole defeat the Axis powers suffered in mainland Europe before the D-Day invasions.

Furious with his Italian allies, Hitler sent his troops in to finish the job. The Nazis’ retribution against the Zagori was terrible. Today, signs point the way to the ‘lost’ villages that were burnt down and emptied.

The redemption of the Zagori began in the 1980s, as wealthy newcomers began to buy up and restore those fine village houses. It was a long haul. This sublime landscape, the Vikos-Aoös, became a national park and then a Unesco geopark. The European Union built roads, including the one from Thessaloniki. Building in the country beyond the village borders was banned. If you built, you had to build with local and traditional materials.

It’s not a romantic story: a tale of committees, lobbying and regulations. But from those years of form-filling and rubber-stamping a wonderful place of immaculate villages, mountain paths and unspoilt countryside emerged.

It just needed a good hotel; and it got a very good one in the Aristi resort. My room was one half of a handsome traditional stone house. Its terrace overlooked steep lawns that met the hillside in a profusion of wild roses and mountain oaks.

That first night, the sun sank comfortably into the distant Adriatic, painting the limestone peaks of the Pindus mountains a luxurious pink. Dinner at the resort’s Salvia restaurant was grilled eel with smoked aubergine followed by trout with butter and almonds, washed down with a resiny, dewy, local white wine. There wasn’t a trace of anything artificial or fancy. The food was as clean as the mountain air.

You get used to disappointments when you travel. Even in the most sublime mountain and beach places, there are traffic jams, fast food trucks, electricity pylons, overpriced restaurants, rip-off hotels.

There are none of these things in the Zagori.

In those five days we drove all day and only saw a handful of cars. We hiked and hiked. Discovery readers know their hikes. For hikers, this is – well, I’m avoiding the word ‘heaven’ with great difficulty.

If you like your hikes to have a bit of culture and lot of scariness, go to the 15th century Monastery of Saint Paraskevi.

It’s a short walk from the village of Monodendri. In the otherwise deserted monastery I ducked into a tiny workshop where the village priest paints and sells icons painted on olive wood. I bought a St Christopher. He is the patron saint of travellers, and I specifically wanted him to look after me because we were about to set off along a bumpy mountain path, no more than three metres wide, that winds 800 metres above the Vikos gorge. YOU PASS AT YOUR OWN RISK, the sign said unnecessarily. I fingered my icon nervously and tiptoed along as close to the cliff as I could get. A shaky 15 minutes later I sat down on a rock outside a tiny hermit’s cave set into the cliff. St Christopher had done his job.

Or if you like an epic day hike with an icy swim and a freezing cold beer at the end, head down into the gorge from Monodendri and emerge in Vikos village several hours later. If you want a gentle walk by a crazy, burbling river, start at the bridge at Voidomatis Springs or take a raft – you’ll get just as much exercise as you fight the rapids and swirls.

All that hiking gives you an appetite. In the Zagori they don’t need locavore hipsters standing in front of blackboards to promote the quality of the produce. It makes sense to grow everything here; and just about everything does grow. Have dolmades (stuffed grape leaves) and grilled lamb at the Sta Riza restaurant in the village of Elati. Try the extraordinary mushroom menu at Canella and Garyfallo in Vitsa – especially in autumn when it’s truffle season. Get a densely packed date sausage at the Sterna café and shop in Kapesovo. Sip a homemade raki – a strong, clear liquor made from leftover wine grapes – on the vine-clad terrace of the Astra restaurant in Megalo Papingo.

As long as people have been writing stories they’ve been dreaming of lands like this: a land beyond the mountains that’s innocent, unspoilt, Arcadian. This isn’t a story. It’s not a myth. The Zagori is a real place and it deserves to be better known.

Fantasy lands beyond the mountains

Sometimes it’s a place in myths and holy texts, sometimes in a novel or a poem. It’s not heaven, but it’s as close as you can get to it on Earth. It’s the land beyond the mountains: idyllic, uncorrupted and, above all, secret.

In the Old Testament it was the land flowing with milk and honey promised to the Jews as they fled Egypt. That idyll was resurrected in the Renaissance. In Greece it’s Arcadia, an area in the Central Peloponnese, 200 kilometres southeast of the Zagori. But for poets such as Dante and Philip Sidney, Arcadia became a place of the imagination, of rural innocence populated by shepherds and nymphs.

As Western writers began to travel, they started to write stories about fantasy kingdoms as their soldiers and merchants colonised the New World. If you went looking for Thomas More’s Utopia, you would begin in Brazil. Real explorers sought the mythical realm of El Dorado, the land of gold, in Guyana and Venezuela. When the British reached New Zealand it was Samuel Butler’s Erewhon (an anagram of ‘Nowhere’), an idyllic but topsy-turvy kingdom hidden behind the peaks.

But the land behind the mountains wasn’t only a Western myth. Tao Yuanming’s poem about a Chinese Utopia isolated from the ordinary world, the Peach Blossom Land, appeared as long ago as 421AD. Then, when English writer James Hilton published his novel Lost Horizon in 1933, he gave the world a new name for an earthly paradise – Shangri La. Yet Hilton explicitly drew on the ancient Tibetan Buddhist Beyul, a place where the spiritual and material worlds meet. It’s a secret land that can only be reached through extreme hardship. And that’s the land we’re all still seeking.