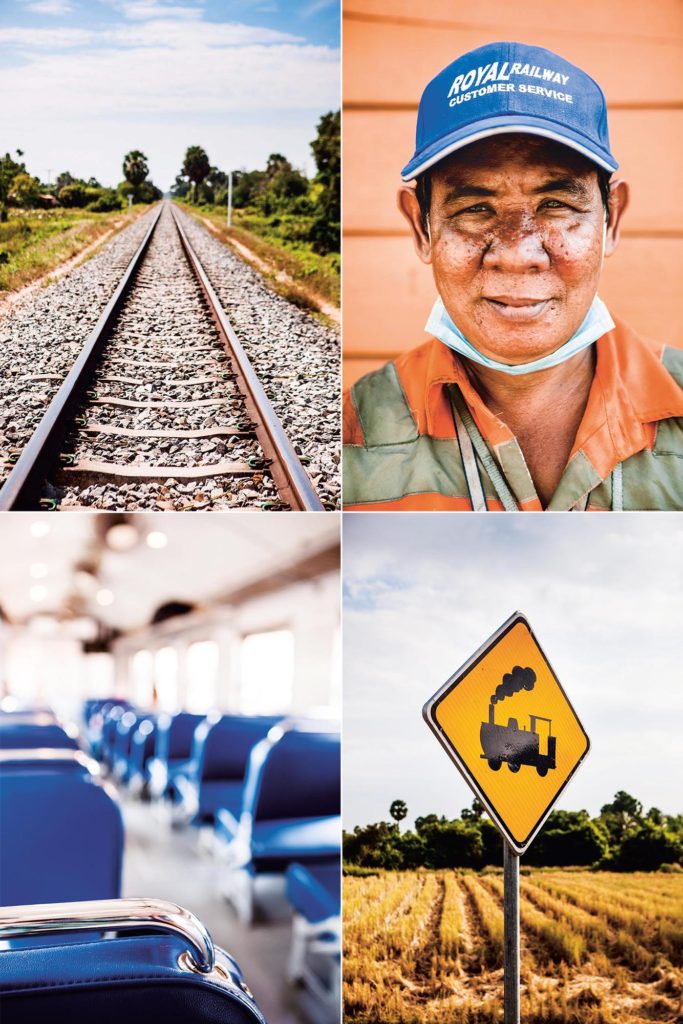

It’s a minute before 3pm, and Ouch Seyha is walking along the platform of Phnom Penh’s art deco Royal Railway Station. A staff member urges the 18-year-old trainee monk to hurry. The train gives a final blast of its horn and Seyha jumps aboard. The passenger service travelling south to Sihanoukville, calling at Takeo and Kampot, pulls away with a sudden lurch.

The teenager makes his way to a window seat. ‘I wasn’t expecting it to leave on time, nothing here does,’ he says. He’s going to visit his parents near Kampot, and a fellow monk recommended he take the train instead of braving National Road 3.

The 266-kilometre train line between Phnom Penh and Sihanoukville reopened last April after a 14-year hiatus. The opening coincided with the Khmer New Year, marking the end of the harvest season. It’s the Cambodian equivalent of Lunar New Year, when Phnom Penh residents zip back to the provinces to celebrate with their families. It seemed like a good time to test the popularity of this reborn railway.

Cambodia has lagged its Southeast Asian neighbours Thailand and Vietnam when it comes to the railways. It’s partly due to the Khmer Rouge ending not even two decades ago, limiting investment and development, and partly due to the country’s squat size. Until now, roads (and rivers) were considered the most viable mode of transport.

The new railway has already found success with a new generation of young Cambodians. For many onboard this was the first time they had travelled by train. For them, the coast is the main attraction. But the journey itself is important, too.

As they rushed onboard, few stopped to appreciate the Phnom Penh train station that has stood for almost 90 years, largely unchanged in a city that has transformed almost beyond recognition recently. Built in the early 1930s, the French colonial-style station has been described as ‘undistinguished’ by unflattering critics. It resembles a turreted white cube, the concrete giving off an air of solemn, calm practicality. To step inside its echoing main hall is to escape the chaos of the rest of the city. The Royal Railway Station once stood as the entry to the French quarter: now it’s the gateway to Cambodia’s southern beaches.

In sharp contrast, surrounding the station are shining towers of banking and government, the evidence of Phnom Penh’s rapid and unsympathetic development push. This new city, spurred by Chinese investment, oversaw the deterioration of the railways. But Cambodia’s imported oil and construction materials needed a way to get to urban areas; and rice and clothing needed a way to get to cargo ships. Plus, the government wanted to push coastal Cambodia as an alternative tourism story to Angkor Wat. The neglected railway offered a solution.

New track had to be laid, new bridges built and boom barriers installed at road crossings to bring the French-built line up to a useable standard. While Cambodia’s rail lines were renovated during the 1970s when the Khmer Rouge ruled, they fell into disrepair in the 1980s, as attacks by the ousted Khmer Rouge guerrillas and chronic underfunding took their toll.

For those growing up in Phnom Penh now, in a world of shopping malls, coffee shops and smartphones, a ride on the train is, ironically, new and exciting.

While the engines are new – to Cambodian rails at least – the two sets of carriages, one blue, one yellow, needed extensive refurbishment. Ignore the air conditioning and the padded blue vinyl cushions that are still recognisable as those that Pol Pot and other senior Khmer Rouge leaders sat on four decades ago. The carriages’ tiled bathroom floors offer a glimpse of a more luxurious era of train travel, while groups regularly hire out the wood-panelled royal carriage of the former King Norodom Sihanouk.

After slowly making its way west through Phnom Penh’s suburbs, the train glides past rice fields still flooded from the rainy season, coconut palms dotting the horizon of the pancake-flat Mekong flood plain. Everyone is taking selfies.

We stop briefly at Takeo station after an hour to let off a young couple visiting their grandparents. ‘It’s been too long since we last came to see them,’ says the man as he hops from the train and helps his wife down, before running to a waiting tuk-tuk.

This small station, little more than a covered shelter, has not yet received the cosmetic upgrades bestowed upon the station at Phnom Penh. No matter. Home to the small hilltop Phnom Da temple, which pre-dates Angkor Wat, languid Takeo offers a more authentic glimpse of Cambodia, away from elephant print trousers and ‘happy’ pizza of the Southeast Asian backpacker trail.

Kampot, another two hours down the line, sits on the bank of the Praek Tuek Chhu river just before it enters the Gulf of Thailand. The ramshackle station, on the edge of town, is graced with a rusting pyramid roof and little else. Surrounded by the eponymous Kampot Pepper plantations and in the shadow of the – relatively – towering Bokor mountains, in recent years the town has served as a weekend getaway for Phnom Penh expats seeking good coffee and river swimming.

The town is as eclectic as it is charming. There are US$3 (HK$23) bowls of handmade pasta made by an Italian chef and served in a shack down a side street; Cambodia’s ‘best’ BBQ ribs at a British pub overlooking the river; and a small cinema that also serves Chinese noodles and dumplings. All are set amid a quiet grid of crumbling Chinese shophouses. You can hear the incessant chatter of swallows swarming around the urban farms where their nests are harvested for soup.

A few passengers get off during the 10-minute stop, and this time one or two get on. From here, the train continues for another two hours to its coastal terminus of Sihanoukville. There is a dramatic change in scenery: gone are the rice fields, in comes forest and flashes of golden sand and the sea.

Named after the late king, Sihanoukville is the gateway to Cambodia’s best beaches – notably Otres, south of the main strip. Many visitors make a beeline for the boats to the quieter islands of Koh Rong and Koh Rong Samloem, a 45-minute trip west.

This renovated rail line is just the beginning. The government announced at the end of last year that a passenger train service from Phnom Penh to Bangkok would begin this spring. Last May, Prime Minister Hun Sen also said that the government would consider building a spur line to Siem Reap, the home of Angkor Wat – which receives four million visitors annually, almost 40 per cent of Cambodia’s tourists. A line to Ho Chi Minh City could be next in the race to connect Southeast Asian cities by rail.

But for now, there are the white sand beaches of southern Cambodia.

Need to know

Phnom Penh to Kampot is US$6 (HK$47) one way; Sihanoukville is US$7 (HK$54). Tickets are available from all stations and via Royal Railway at +855 0 78 888 582.

Trains run both ways Saturday and Sunday, with a Phnom Penh to Sihanoukville service on Friday afternoon. Additional services run during Cambodian national holidays.