‘Listen to that magpie.’ Antony Gormley is standing on the flight of steps set into the exterior of his studio, looking towards one of the London plane trees growing in the courtyard. The last of the afternoon sunshine is falling on his 67-year-old face. It’s hard to make out the bird he hears in the branches, though something is giving off quite a squawk.

The artist looks towards the sun as it sets behind a neighbouring block, and tells Tina, the photographer, when she’s likely to catch a good shaft of light. ‘Sun!’, ‘It’s gone again,’ ‘Sun!’, ‘I think you’ve got about a minute of it left.

Interviewing Gormley is a one-sided dialogue. Unlike some artists, he is very good at explaining his work and its place within art history. The thinking behind his new show, Rooting the Synapse – which opens this month at Hong Kong’s White Cube gallery to coincide with Art Basel Hong Kong – comes slower than his better-established thoughts on recent Chinese history, the Catholic Church or the merits of the European Renaissance. Nevertheless, it’s all very clearly resolved in Gormley’s mind, and any hint of a mistimed interjection is politely resisted until his point is made.

We talk in a white-walled room on the upper floor of his studio complex. There are no windows: ‘I don’t want a view,’ he says. ‘This is an internal world where we are going to reinvent the world.’ There’s a pile of clay at the far end arranged into the shape of a squatting man, a table and chairs at the near end, a few paint brushes, a copy of the famous plaster cast (or ‘life mask’) of the great British romantic poet and printmaker William Blake, as well as a computer, a chest containing illustrations and drawings, a desk phone, a CD player and a good selection of CDs: some Bob Dylan and David Bowie, as well as some Indian ragas and recordings of classical works by composers such as Henry Purcell.

The building was designed by the British architect David Chipperfield, and is wonderfully smooth and bright. However, once you get over its floor area – 10,000 square feet – it isn’t especially showy. Unlike many contemporary artists, Gormley isn’t interested in surface beauty and visual effects, but instead in an inner sense of ourselves.

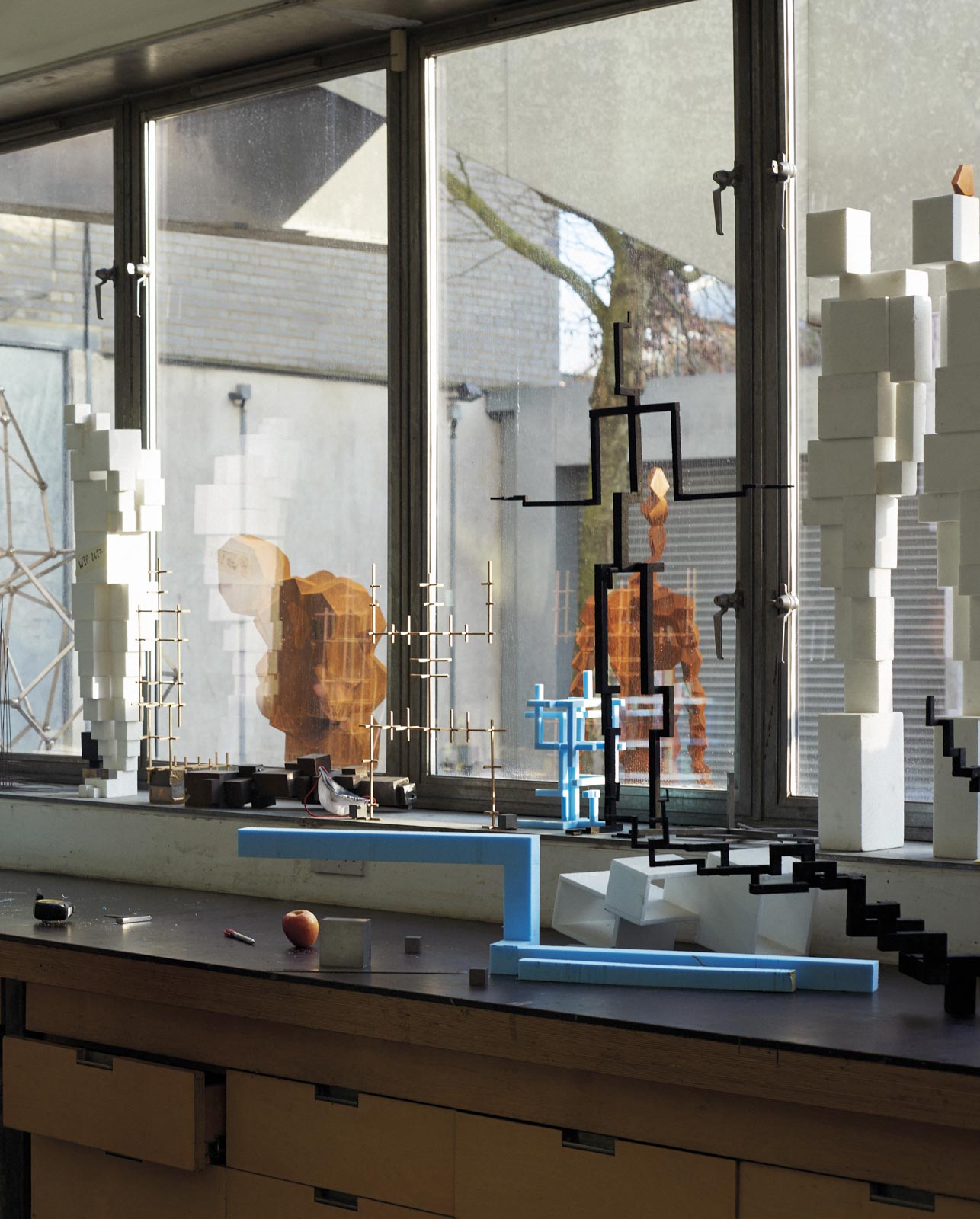

The works in his new show, like many others by the artist, are upright sculptures the size and shape of Gormley’s own body. These new ones aren’t solid forms, but kinking, almost neo-cubist networks of angular iron rods that fill

out into a human shape.

He hopes the sculptures will give rise to a way of thinking about the body ‘less as an object of idealisation or a carrier of beauty’, he says, and more as ‘a place of transformation of energy, of unknown connectivity’.

‘I think of these works being a bit like crooked TV aerials,’ he explains, ‘signalling or receiving projections from the viewer; or signalling states of embodied minds out into the world, with no need for narrative or representation – but simply saying, here is space that has few characteristics, that is about how mass and space interconnect. Can sculpture in its stillness be a tool or instrument by which we attend to our own being in space and time? That’s the ambition.’

It’s an ambition that Gormley has harboured for a very long time. ‘I always wanted to make things that are somehow both a charting and an investigation of how it feels like to be alive,’ he says, ‘I’ve always done that since I was tiny.’

Antony Mark David Gormley was born on 30 August 1950 in the London borough of Camden, the same borough his studio now occupies. His Irish father, a businessman in the pharmaceutical industry, and German mother chose Antony’s name partly because its initials AMDG matched the Catholic motto, ad majorem Dei gloriam – ‘to the greater glory of God’.

‘I spent a lot of my pre-puberty years praying to plaster virgins in various second-rate Catholic churches around North London or Chichester,’ he says. Gormley is not fond of the religion, describing it as ‘a strange mixture of sentimentality and actual cruelty’.

He discovered much better spiritual instruction in India. Gormley visited following his graduation from Trinity College, Cambridge, and developed a strong interest in Buddhism.

‘It was a much more pragmatic thing,’ he says. ‘Let’s just watch the breath, let’s watch a feeling arise, whether it’s pleasure or pain, and try not to identify with it. It’s not my pleasure or my pain, it’s a pleasure or pain – watch it rise and watch it disappear.’

He concentrated on the Vipassana tradition, common in Myanmar and not unlike the Buddhism favoured in China. Gormley has visited Chinese Buddhist monasteries: he even developed a musical performance piece with the Shaolin monks of Henan province.

This thinking stayed with him on his return to Britain, when he began his career in earnest. He made the first sculpture of himself in the 1980s, while living in a squat not far from his current studio; these early pieces earned him great critical acclaim but little money. He signed up with his current gallery, White Cube, in 1993; in 1994, he won the Turner Prize, Britain’s most prestigious contemporary art award; in 1998, he completed his most famous public sculpture in the UK, Angel of the North, a 20-metre-high steel figure with a wingspan roughly the same as a jumbo jet’s, which stands on the outskirts of Gateshead in the northeast of England.

His more recent installation Event Horizon (2007) caused greater controversy when the life-size figures he set into prominent locations in London, New York, Hong Kong and elsewhere were mistaken for suicide attempts. Infamy was never his intention. Instead, Gormley states his long-term ambition as ‘somehow reanimating the possibility of the body in art, particularly in sculpture, without descending into storytelling and sexualisation’.

He’s especially dismissive of the ways we present ourselves on social media. ‘We are surrounded by the proliferation of imagery that comes from a late capitalist system that wants to persuade us that we need things that we don’t need,’ he says. ‘It’s a shame if we then become competitive purveyors of the very same thing that the advertising industry is forcing upon us.’

In Gormley’s mind, the selfie might show the body, but misses deeper aspects. ‘Most of us wake up in the morning, grab our mobile phones, see what our duties for the day are and spend the day fulfilling them,’ he says, ‘while this alternative system of intelligence and engagement with the world is doing its own thing, to which we pay almost no attention.’

Gormley’s wiry new works might just let us all switch off a little, and attend to that unexamined inner space.

Rooting the Synapse is at White Cube during 27 March-19 May, whitecube.com