For an institution that’s been dead almost 160 years, Britain’s East India Company is staging quite a comeback. An Indian entrepreneur has relaunched the company as a 21st century symbol of sophisticated consumption (more on that later), while actor Tom Hardy has put the company at the centre of his Georgian noir drama, Taboo.

Founded in 1600 by Queen Elizabeth I, the company had one mission: to break into the luxury markets of Asia. Over the next 250 years, it changed the course of economic history, creating a business empire stretching from London and Kolkata, then onto Singapore and Guangzhou. Like corporations today, it revolutionised lifestyles – in its case, with exotic spices, textiles and tea. But it also became infamous for its corruption, using its vast private army to conquer India, and for masterminding the illegal opium trade with China.

So what explains the renewed fascination? In my book The Corporation that Changed the World, I describe an organisation that rose to dominate world trade. All the questions we ask of today’s corporate giants – about the wealth of their executives, their stock market bubbles, their tax schemes to maximise profits and the way they treat both employees and communities – are presaged in the story of the East India Company.

Taboo is a work of fiction. But it has important echoes in the real story of the East India Company. Here are nine snapshots taken from the company’s almost three-century-long history that give an insight into the character of this world-shaping corporation.

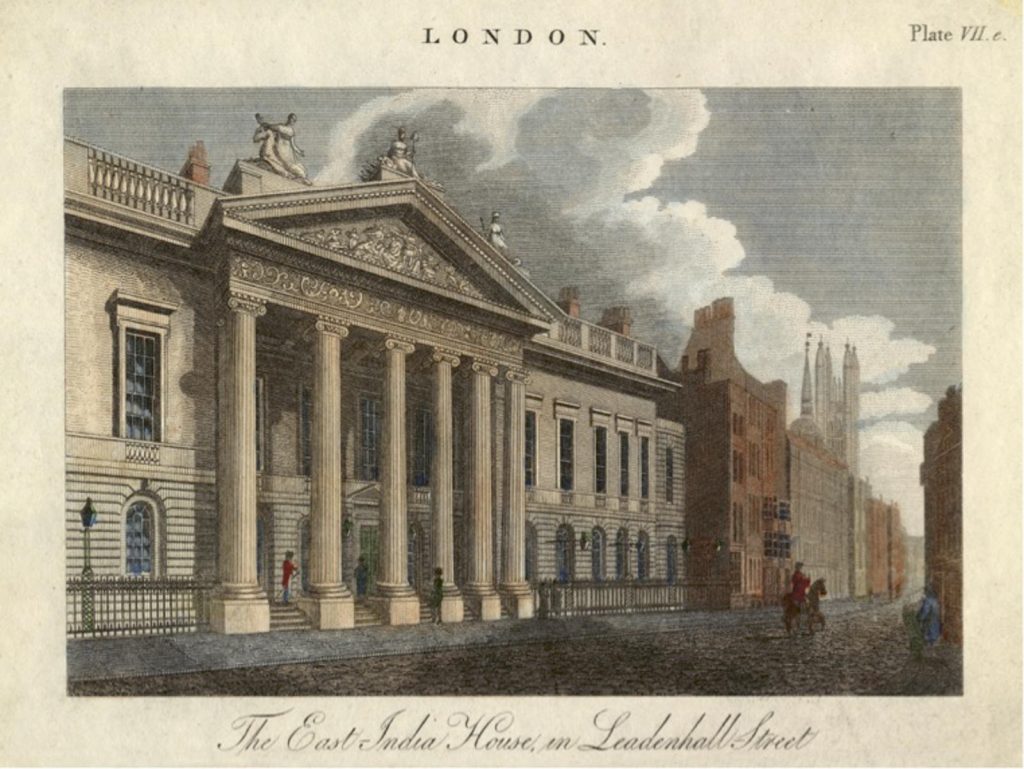

1. The opulent HQ

From its headquarters on London’s Leadenhall Street, the company came to manage a global empire. It was here in the grandiose East India House that its directors met each week and where its famous auctions were held each quarter

to sell its prized commodities. Constructed in 1729 and rebuilt in 1800, the building was torn down in 1861, a mere three years after the company had come to an end. To get a sense of the scale of East India Company architecture that still exists, look no further than the Writers’ Building in Kolkata, now the seat of West Bengal’s government, built in 1777 to handle its Indian operations.

2. Bengal muslin

The company was in the import-export business, shipping out silver and gold in return for Asian goods. Like its peer in the Netherlands, the Dutch East India Company, the British company first concentrated on the spice trade before diversifying into Indian textiles. New products – and words – poured into Britain: bandana, calico, chintz, dungaree, gingham, seersucker, taffeta. British weavers rioted to prevent this flood of cheap Asian imports and trade barriers were introduced, but Bengal’s muslin remained prized above all. It’s hard to imagine Jane Austen’s heroines without the handiwork of India’s weavers. In Bangladesh today, garment workers still remember the company. But the memory is one of cruelty: ‘They were the people who cut off our weavers’ thumbs,’ one told me.

3. The Battle of Plassey

The company’s domination was achieved by a mix of intrigue and force of arms. The pivotal moment took place on 23 June 1757, when the company’s army defeated the ruler of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey. In this painting, the company’s leader, Robert Clive, meets with Mir Jafar, the general who defected to the East India Company in return for the throne of Bengal. (Even today, to be called a Mir Jafar in Bengal is to be accused of the worst sort of treachery.)

Often seen as the battle that established the British Empire in India, Plassey is actually the company’s finest business deal. For his dealings, Clive netted the equivalent of £25 million (HK$249 million) for himself in today’s money, with a windfall of £250 million (HK$2.49 billion) for the company. This was sensational stuff: a private company now controlled a major empire’s richest province. Clive wrote to the company’s directors after Plassey: ‘This great revolution, so happily brought about, seems complete in every respect.’

4. Imitation Teapots

Tea became the company’s main source of profit. The British craze for tea grew steadily from the 1660s, with consumption doubling every 18 years in the 1700s. The problem was that these fragrant leaves could only be sourced from China, and the company was only allowed to send its merchants to a single city – Guangzhou (known then as Canton) – for a few months each year.

Of course, the prized bohea, congou,

souchong and pekoe teas had to be drunk in the right sort of (pricey) china cups. Their cost drove British entrepreneurs to imitation, like this bizarre teapot from the 1760s, made at the New Canton factory in London’s East End. The company’s tea generated a new meal in the English day – teatime – but across the Atlantic it sparked another revolution. On 16 December 1773, 40 tonnes of Chinese tea bought with Indian silver and owned by a British corporation were dumped into Boston Harbour by protestors dressed as Native Americans.

5. Opium

The challenge for the company’s executives in Leadenhall Street was how to staunch the ever-increasing flow of silver into China to pay for its tea. China was too big to conquer by force. Instead, it was contraband that turned the tide: opium. Here we see two labourers carrying an opium chest, with the company’s logo stamped on the side.

It was Warren Hastings, the first governor-general of Bengal, who first tried smuggling in the early 1780s. His attempts to sell surplus opium in Canton were a complete failure, however. The narcotic flood truly took off in the early 19th century. Grown under company monopoly in India, the opium was auctioned to private traders and then smuggled into China. When China clamped down on the trade in 1839, war broke out, with Britain intervening to protect the ‘free trade’ in opium. Two Opium Wars later, Hong Kong was established as a British colony and all controls on opium were removed, resulting in millions of addicts in China.

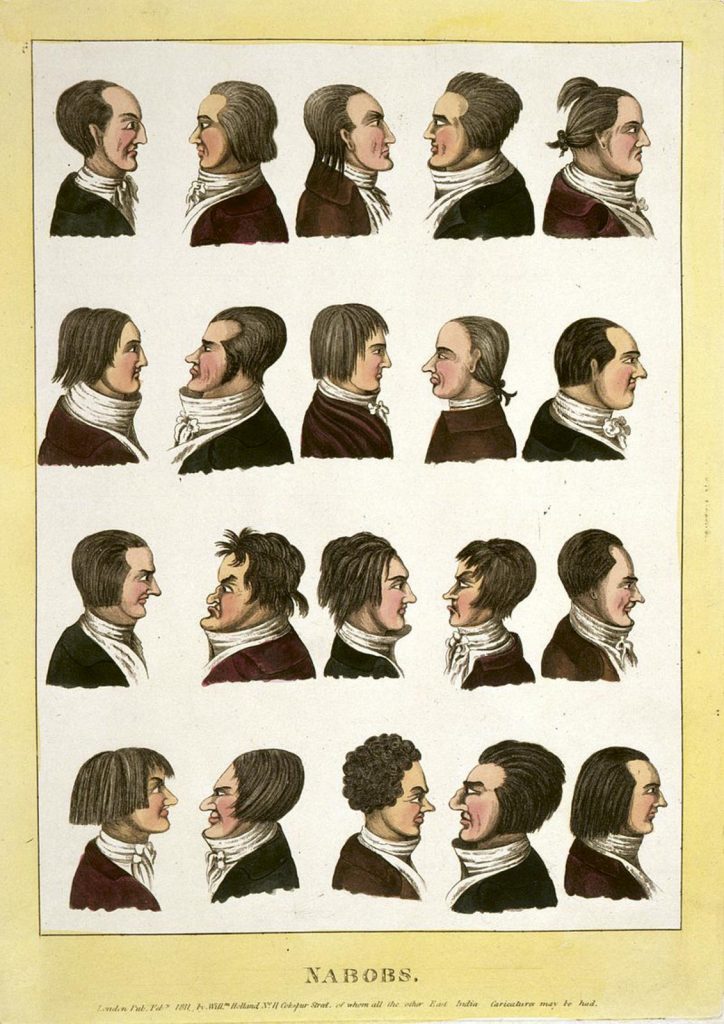

6. The Nabob

The wealth the company generated and the lifestyles it fashioned were soon the targets of Augustan satire. Opening at London’s Haymarket Theatre in the summer of 1772, The Nabob was a lighthearted jest at the expense of the new generation of company executives returning from India. A corruption of the Hindi word for prince, nawab, these ‘nabobs’ were the yuppies of their day – young, rich and throwing their money around, marrying into the aristocracy and buying their way into parliament.

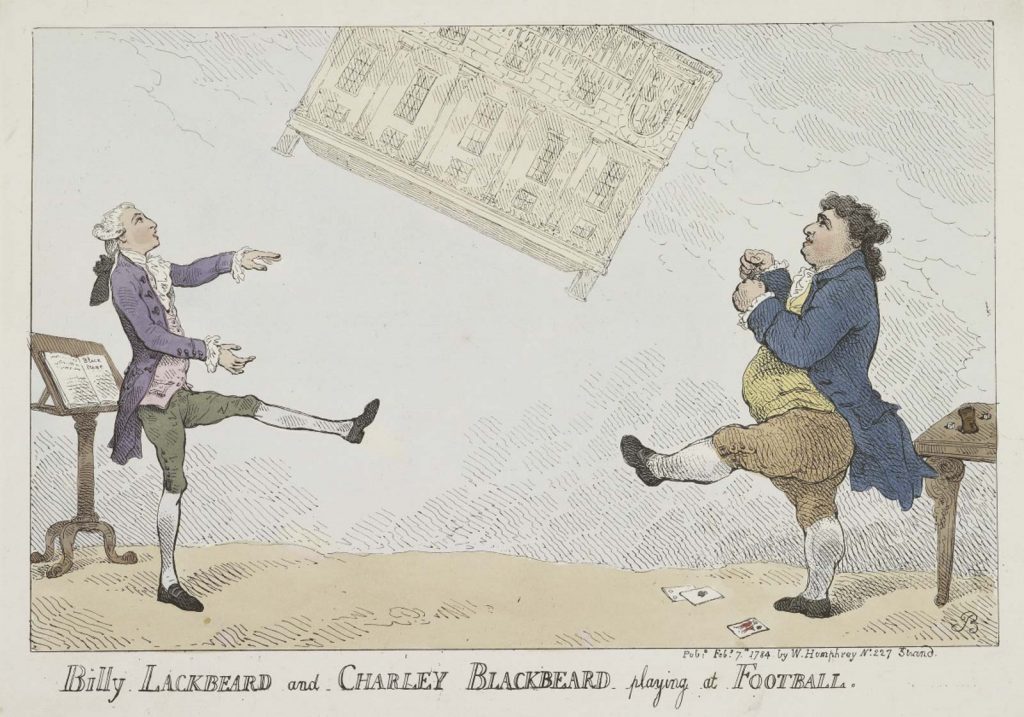

7. Political football

The company’s fate was ultimately decided in parliament, as the British state wanted to tame this rogue corporation and get its share of the wealth. This 1784 cartoon is perhaps one of the earliest depictions of political football in the public consciousness. In the centre is East India House, being kicked to and fro by the Conservative prime minister William Pitt (on the left) and the Whig Charles James Fox (on the right). Fox had proposed a new law to decapitate the company, replacing its directors with parliamentary commissioners. Pitt united with the Crown and the City to block the bill. In the resulting election that year, rumours swirled that East India Company money was deployed to elect sympathetic MPs. Pitt was returned to power and passed a much milder set of measures to tame this wayward corporation.

8. The Tiger of Resistance

One of the most sustained attempts to hold back the company’s expansion came in southwest India in the form of Tipu the Tiger, Sultan of Mysore. Tipu was known as ‘the Terror of Leadenhall Street’, defeating the company’s army, modernising his state and negotiating alliances with revolutionary France to combat their shared enemy. His hatred of the British is expressed in this gory mechanical organ the sultan had made, which would even growl as it chewed the body of a company soldier. But even Tipu proved no match for the company’s cunning and military muscle: he died fighting in Srirangapatna in 1799. The organ headed back to Britain and was put on display in the company HQ’s museum; it’s now in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

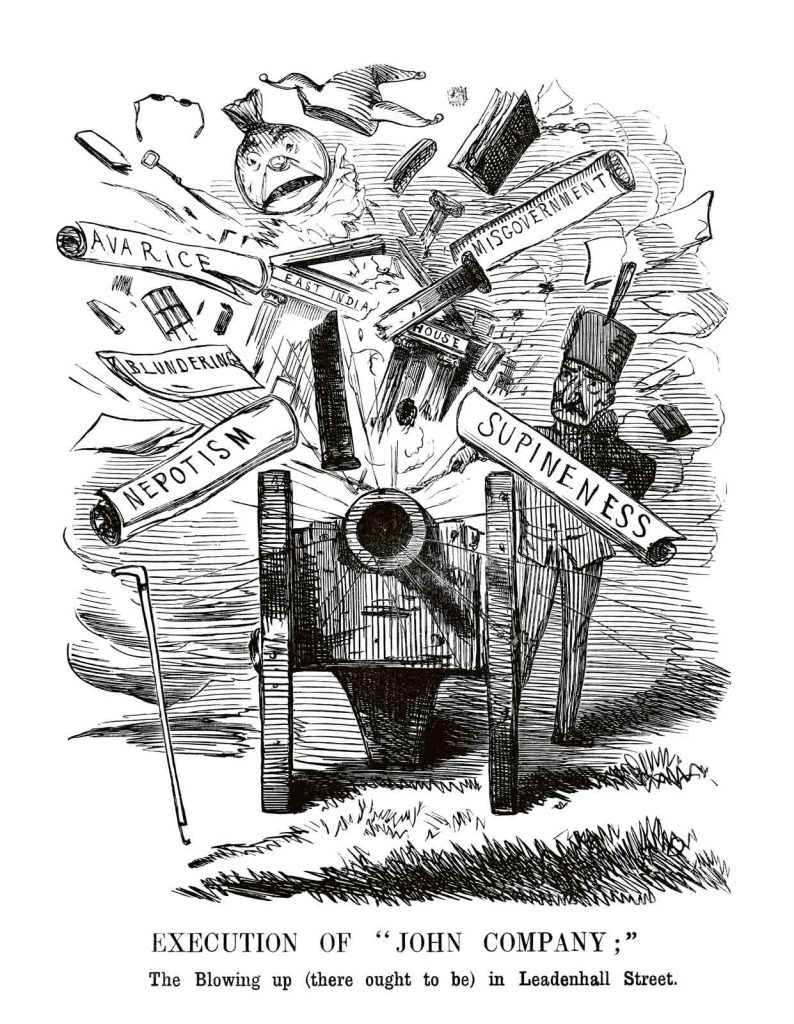

9. An inglorious end

The beginning of the end came in 1857 with the uprising of the company’s soldiers against its growing arrogance and scorn for Indian culture. This contest was horrifically bloody, with prisoners often blown from the ends of cannons. Back in London, there was a backlash against the company for its incompetence, depicted here by Punch magazine. In the background, you can see the classical facade of the headquarters being blown up, along with its crimes and misdemeanours. The company’s leading executive, John Stuart Mill, pleaded for a stay of

execution. But on 2 August 1858, parliament effectively nationalised the company, marking the start of the British Raj. Mill would go on to use his generous company pension to write his classic works on liberty and women’s rights.

Risen from the ashes?

The company might be long gone but its legacy remains. A few years ago, Indian pan masala brand Rajnigandha ran a TV advert in which an Indian tycoon drives through a port city and passes a building emblazoned with the name East India Company. He asks his chauffeur to stop and declares, ‘I want to buy this company. They ruled us for 200 years and now it’s our turn.’ In many ways, businessman Sanjiv Mehta actually did this in 2010, opening up a shop in London’s West End, selling luxury food and tea under the revived East India Company brand. To turn a firm that once owned his nation to one owned by an Indian national was, for Mehta, ‘a dream come true’ and a sign that there’s life yet in the ‘Honourable Company’.

Find Taboo in TV (drama) on the interactive menu onboard